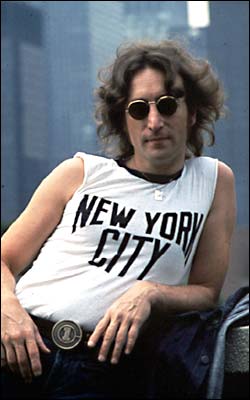

MOURNING 1980

|

Unfinished Music: John Lennon, New Yorker, in December 1974.

(Photo: Bob Gruen/Starfile) |

Everybody who was older than 10 in 1980 remembers the basic facts. It was early December. A Monday. A football game was on. New England was lining up for, or had just kicked, what seemed at the moment like a very important field goal. And Howard Cosell announced to America that here on the streets of New York, John Lennon had been shot dead.

Staggering shock and despair. A week of ghoulish tabloid front pages (including, naturally, the Post’s going with a page 1 photo of his dead body in the morgue, a trickle of blood rolling out of the corner of his mouth). Finally, the following Sunday, a silent, ten-minute vigil—100,000 in Central Park, millions more around the globe. And then the world got back to its work. But those six days of mourning began to reveal to us just how much, and in what ways, John Lennon had helped reshape the world.

First, some context worth remembering: Lennon at that point was, of course, beloved by millions of fans, but he was not yet the universal and irreproachable icon he later became. To the government, and to what used to be called the Establishment, he was a rabble-rousing druggie radical. Richard Nixon and J. Edgar Hoover had wanted him thrown out of the country (he prevailed, claiming his green card in 1975). Likewise, Beatles stock, in that era of disco and punk, was arguably at an all-time low. Liverpool even tore down the famous Cavern Club in the late seventies; it was only later that the city fathers understood the importance—and the commercial potential—of the Beatles as a point of civic pride (as if there were other reasons a person would go to Liverpool?) and hastily rebuilt the place.

But all that came later. The America of 1980 had lately taken a turn against more or less everything Lennon had stood for. A month before Lennon’s death, the country voted overwhelmingly for Ronald Reagan. As it happened, President-elect Reagan was in New York the day after Lennon’s murder, visiting Cardinal Cooke and having a much-publicized family-values lunch with Ron Jr. He pronounced Lennon’s death “a great tragedy,” which was comic, really, because it was hard to imagine that Reagan had more than the vaguest idea of who John Lennon even was, and to the extent that he did know, he obviously must have found him disgusting. Reagan added quickly that no, the shooting did not make him rethink his views on gun control. Expressing a local variation on the theme, Brooklyn Republican city councilman Angelo Arculeo blocked a tribute to Lennon at the City Council, complaining that he didn’t “recall these kinds of tributes being extended to Bing Crosby, who really was an American legend.”

Lennon’s murder is usually described as the end of something—the real end of the sixties, finally; the end of the dream. But time has made it clear that his death and the mourning it provoked also constituted, in their way, a beginning. Lennon symbolized things that Ronald Reagan and Angelo Arculeo didn’t care for or understand, changes they were trying to push back against. These things were, as much as William Bennett might dislike the use of the term, values: doubting authority, breaking rules that deserved to be broken, and seeing, always, the absurdity in it all (including your own part in it).

The massive and unutterable grief on display in New York and around the world that week—and the celebrations of his life and music—showed that those values had taken hold to a degree that society had not yet reckoned with, that they were just too important to too many people. Those values have had their ups and downs since—down in the political realm, for now, but doing quite nicely in the larger culture—and the ups have happened, of course, largely for demographic reasons (the dying-off of the Glenn Miller generation, the Beatle generation now running things). But the way Lennon was killed—assassinated, like King and the Kennedys—and the way he was mourned made for what is in retrospect a symbolically important moment: the moment when Lennon values ceased to be merely generational and started to become universal. He would have been 62 now, and what an interesting New Yorker he’d be, especially in these times. Would he be playing antiwar rallies? Might he have finally shared a stage with Paul at that post-9/11 concert? At the very least, he could have made him write a better song than “Freedom.”