|

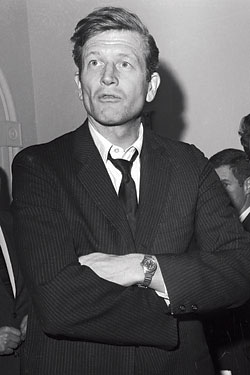

1968: John Lindsay, confronting a garbage strike.

(Photo: Bettmann/Corbis) |

New Yorkers have pretty much always felt elegiac about the transformation of their city, with alarmist peaks every half-century or so. (And given that we’re now approaching the half-century anniversary of the alarming start of the last prolonged New York’s–going–to–hell era, our present Wall Street horror show looks uncomfortably familiar.) Although Henry James was a New Yorker only briefly and involuntarily, as a child in the 1840s and 1850s, and chose to live most of his life in Europe, people think of him as a chronicler of New York. And that’s because of two books—the novella Washington Square, set in the quaint Knickerbocker burg of his childhood, and the nonfiction The American Scene, which contains his melancholic and disgusted 40,000-word account of returning at age 61 to an utterly transformed New York.

In the time since James was a boy, the city’s population had grown from 500,000 to almost 5 million, resulting in a “consummate monotonous commonness, of the pushing male crowd, moving in its dense mass,” a monstrous incarnation of the “will to move—to move, move, move, as an end in itself, an appetite at any price.” Skyscrapers of 20 and 25 stories (“the detestable ‘tall building’ … and … its instant destruction of quality in everything it overtowers”) had arisen, and the underground train system (“the desperate cars of the Subway”) had just opened. “The terrible town,” this “remarkable, unspeakable New York,” now had a large Jewish ghetto in which the streetside fire escapes created “a little world of bars and perches and swings for human squirrels and monkeys.”

“I have the imagination of disaster,” James wrote elsewhere, not long before his brief return to New York, “and see life as ferocious and sinister.”

By the 1960s, middle-class New Yorkers were not merely saddened by their city’s coarse, exotic new hurly-burly, they felt besieged, in fear for their lives as well as their lifestyles. The disaster felt actual. Americans at large were discombobulated, of course, between 1964 and 1968, by several sudden changes—the war in Vietnam, the counterculture, the spasms that followed the civil-rights movement. But New York at the same time entered its own particular perfect storm—radical economic and demographic change, plus governmental dysfunction, plus an increase in violence so exceptionally steep and sudden it was almost as if war had broken out.

Imagine the unsettling Rip Van Winkle sensation of being a New Yorker in 1968. Two decades earlier, the city had been a thoroughly working-class place, with more manufacturing jobs than anywhere else in America, but most of those factories and their jobs had disappeared, leaving a city of office workers and the poor. And now the white-collar good times were looking iffy: At the beginning of 1966, Wall Street’s postwar boom reached its top. In just eight years, between 1960 and 1968, the city’s population had gone from 14 percent to 20 percent black. And during the same eight years, murders in the city had increased from about one a day to nearly three. In the winter of 1966, the subways and buses were shut down by a strike, followed over the next two years by a sanitation strike and two teachers’ strikes. All were bitter—especially the second teachers’ strike, which grew out of a fight between mostly Jewish teachers and mostly black parents over community control of Brooklyn schools.

But if you were young or youngish and had a sense of fun or adventure, it was the best of times as well as the worst. This magazine in its early years specialized in chronicling local crimes and life going haywire, yes, but catered just as obsessively to the eager new mob of proto- yuppies and bourgeois bohemians gorging on the swingy new New York, the people scrambling to eat the best food and wear stylish clothes and buy cool tchotchkes, to see the smart new art and movies and plays and comedians. In 1968, Elaine’s was still new, and in the Fillmore East’s first two months of existence Janis Joplin, the Doors, the Who, Frank Zappa, Traffic, and Jefferson Airplane all performed.

In a Times article that year about what a “startlingly expensive place to live” New York had become, the reporter marveled at the nutty Manhattan prices: On the West Side, for God’s sake, six-room co-ops were selling for $50,000 and “unrenovated brownstones” for $100,000—around $300,000 and $600,000 in today’s dollars.

And while the cohort that essentially dreamed up contemporary New York (and, not coincidentally, New York) were mostly members of the nameless generation that came of age between V-J Day and the creation of the Mets, there was a huge pool of younger would-be neo–New Yorkers in the pipeline, drawn to the sexy flicker and buzz of the groovy, glamorizing metropolis: In 1968, the oldest baby-boomers were just graduating college and the youngest were just starting school.