|

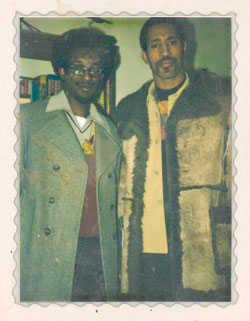

Coke La Rock, left, and D.J. Kool Herc at 1520 Sedgwick in the early seventies.

(Photo: Coutesy of Cindy Campbell) |

On August 11, 1973, in the rec room in an unassuming brick apartment building at 1520 Sedgwick Avenue, hard by the Major Deegan Expressway, a 16-year-old Jamaican immigrant changed pop music forever. This is the night that Clive Campbell, later known as Kool Herc, invented hip-hop at his little sister Cindy’s “back to school jam,” which was actually a moneymaking venture to fund a shopping expedition to Delancey Street.

For the hip-hop faithful, the story of that party is something close to sacred, but the bland building itself had sunk into obscurity. As had Herc himself, who never cashed in on the rhythmic innovations that ultimately led to the blingy universe of Puffy and Jay-Z. But lately both Herc and his old house have been back in the news, after a private-equity firm tried to buy 1520 and take it out of the state’s Mitchell-Lama middle-class-housing program. This would lead to higher rents, which alarmed housing activists. When they realized that this was no ordinary building, they called in Herc to help get the media’s attention, and possibly prevent the sale.

Herc hasn’t lived there in twenty years. “We still keep in touch with people from 1520,” Cindy Campbell says. “When one of the original tenants called me last year and told me that they had received notice that they had to be gone within the year, I knew we should be involved.”

On August 6, the 53-year-old Herc—still muscular, clad in a red T-shirt, and black jeans—held a press conference with Senator Chuck Schumer (who called him “LL Cool Herc” by mistake) and other politicians. It was a strange alliance, but it made the earnest topic of affordable housing more newsworthy. During an earlier press conference, Herc had said, “It’s like Graceland or the Grand Ole Opry; it’s the birthplace, where it all started from. It’s a piece of the American Dream and we just want to preserve it.”

Cindy’s back-to-school party took place in a very different Bronx, one that private-equity firms were most definitely not interested in. “I can’t speak about the rest of the country, but the Bronx in 1973 was crazy,” said Herc’s friend Coke La Rock, who also played a pivotal role that night. “Anybody that tells you different wasn’t here. Buildings were burning, Vietnam vets were coming home messed up, there were street gangs. It was like that movie The Warriors.”

Nationwide, revolution was in the air, Afro picks were in the hair, and Fat Albert strutted Saturday mornings on CBS. Blackness was beamed onto countless movie screens as anti-heroes the Mack and Black Caesar “stuck it to the man.” The realism of Stevie Wonder’s “Living for the City” and Donny Hathaway’s “Someday We’ll All Be Free” blared from the radio.

Herc, who’d been given his nickname by friends who played basketball with him (it came from the cartoon The Mighty Hercules), was a D.J., like his father, who had a business playing at parties. “My father shared his love for music,” Cindy says. “He played everything from Nat King Cole to Pat Boone. For my dad, there was no color barrier when it came to records; good music was just good music.” Herc listened to Cousin Brucie on WABC, who played acts like Crosby, Stills & Nash and Three Dog Night.

Herc had been refining a new technique in his second-floor bedroom: He’d ignore the majority of the record and play the frantic grooves at the beginning or in the middle of the song. Herc referred to this as “the get-down part,” because this section of the song was when the dancers got excited. Utilizing two turntables and a mixer, Herc used two copies of the same record (removing the labels so others couldn’t “steal” them) to isolate and extend the percussion and bass. This became known as “the break.” It wasn’t until he was spinning at his sister’s party that he showed it to an audience.

That night, Cindy rented the recreation room for $25, and charged admission. “It was only 25 cents for girls and 50 cents for the guys,” she says. “I wrote out the invites on index cards, so all Herc had to do was show up. With the party set from 9 p.m. to 4 a.m., our mom served snacks and dad picked up the sodas and beer from a local beverage warehouse.” Herc had brought new records from a shop called Sounds and Things and had practiced for most of the week on his father’s Shure speakers.

But something else, unplanned, happened that night: La Rock began “rapping.” Wearing spotless new Adidas pants from Harlem store A.J. Lester’s and sporting a fresh haircut he had gotten at Dennis’ Barbershop over on Featherbed Lane that night, La Rock picked up the mike and began talking over the blaring breaks.