|

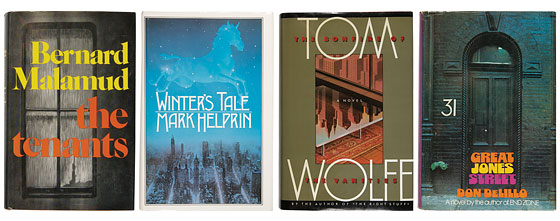

Books Courtesy of Argosy Book Store and Strand Book Store.

(Photo: Stewart Isbell) |

New York is a hypertextualized city. By 6 a.m., our commuters have smudged more words off their papers than most cities read all day. How to even begin identifying a canon? While reading, I plotted candidates along two mystical axes: one of all-around literary merit, and the other of “New Yorkitude”—the degree to which a book allows itself to obsess over the city. Robert Caro’s The Power Broker just about maxes out both axes; others perseverate so memorably on smaller aspects of city life that they had to be included. There were, of course, regrettable omissions: Jimmy Breslin is a quintessential New York writer whose main strength is not books; Puzo’s Godfather was better as a movie. Below you’ll find the books that we think best embody the city’s most sacred pastime: paying deep attention, then translating it all into words.

NORMAN MAILER, THE ARMIES OF THE NIGHT, 1968

Although most of the book’s action—Mailer’s rabble-rousing at a protest march on the Pentagon—takes place 200 miles south of the city, this still belongs in the New York canon. Late-sixties Mailer was a titanic New Yorker at the height of his New Yorkiness—he ran for mayor the year after Armies came out—and this remains the most convincing fusion of his literary talent and social exhibitionism.

RON PADGETT AND DAVID SHAPIRO, EDS., AN ANTHOLOGY OF NEW YORK POETS, 1970

It’s an open question whether the so-called New York Poets, a loose cluster of playfully surreal post-Beats (O’Hara, Ashbery, Koch, Berrigan, et al.), actually cohered in any meaningful way: a unifying disunity that is itself, if you think about it, very New York.

BERNARD MALAMUD, THE TENANTS, 1971

Harry Lesser, a Jewish novelist, is the last resident of a Manhattan tenement slated for demolition—until a militant black novelist starts squatting in the apartment next door. A feverish parable of mutual racist destruction, The Tenants manages to fight off some serious seventies impediments (didacticism, dream sequences, drug fantasies, and outmoded sex lingo: “I wouldn’t mind laying some pipe in her pants”) to capture, as well as any novel has, the existential precariousness of New York real estate.

CHARLES MINGUS, BENEATH THE UNDERDOG, 1971

Charles Mingus was categorically uncategorizable: white, black, Asian; bassist, bandleader, composer; L.A., New York. He always insisted that his music was not jazz: It was Mingus music. This whacked-out half-fictional memoir (cf. his early experiences as a pimp) is not autobiography: It’s Mingus writing. It makes today’s fictioneering memoirists look like stenographers, and vacuum-seals the mid-century scene’s flavor more potently than mere fact ever could.

ROGER KAHN, THE BOYS OF SUMMER, 1972

Kahn’s stylized memoir of his years reporting on Jackie Robinson’s Brooklyn Dodgers kills two oppressive pterodactyls with one stone: It is not only by far the best book ever written about the team but also the best evocation of Brooklyn’s Golden Era—before the Fall, the Flight, the Fires, the Filth, and our cheesy “Fuhgeddaboudit!” revival.

DON DELILLO, GREAT JONES STREET, 1973

Bucky Wunderlick, the world’s most famous rock star, escapes his public by holing up in a squalid apartment on Great Jones Street—a setting that inspires DeLillo’s most focused meditation on New York, a “contaminated shrine” of rubble, warehouses, and oil-drum fires that seems “older than the cities of Europe, a sadistic gift of the sixteenth century, ever on the verge of plague.” (The plague, apparently, was gentrification: 35 years later, Great Jones Street is home to a luxury spa with its own three-story indoor waterfall.)

GRACE PALEY, ENORMOUS CHANGES AT THE LAST MINUTE, 1974

Paley was a politically active child of Russian Jewish immigrants; her sad, witty stories are set in a lost Manhattan of lefty idealists. But they never come off as tracts: They’re more like electric scraps of dialogue overheard in a crowded diner.

ROBERT A. CARO, THE POWER BROKER: ROBERT MOSES AND THE FALL OF NEW YORK, 1975

Caro’s heroically thick account of the construction and demolition of the soul of Robert Moses has itself become a Moses-esque monolith: the heaviest book on many New Yorkers’ shelves, and the textual thruway on which all other popular histories of the city’s power brokers still drive.

WOODY ALLEN, WITHOUT FEATHERS, 1975

Allen’s comic persona—that giant parade balloon of stuttering neurosis bobbing permanently over our skyline—was made famous by his films, but it originated in old-timey magazine humor writing. This collection of brief exercises in illogic—see especially his brilliant “If the Impressionists Had Been Dentists”—is still his most natural and satisfying work.

E.L. DOCTOROW, RAGTIME, 1975

Turn-of-the-century New York is the historical novelist’s bread and butter: downtown slums, uptown mansions, and free-for-all lawlessness. In Ragtime, Doctorow’s historic attempt to sabotage the historical novel, the scenery is the same, but the characters, including Houdini and Emma Goldman, move with an unpredictable, ahistorical fluidity that feels deeply right—particularly at the inscrutable turn of another century. (See Q&A, here.)

SUSAN SONTAG, ON PHOTOGRAPHY, 1977

After Lionel Trilling, Sontag was New York’s reigning public intellectual. On Photography appeared just as the city’s image density began to outpace its population density; today, as our digital cameras shrink and multiply, its insights are even more relevant. (It’s also chock-full of great lines to shout out next time you’re snapping cell-phone pictures of your mom posing with the naked cowboy: “To photograph someone is a sublimated murder!”)

REM KOOLHAAS, DELIRIOUS NEW YORK: A RETROACTIVE MANIFESTO FOR MANHATTAN, 1978

Koolhaas’s playful, brilliant, nutty, image-stuffed, aphoristic history of Manhattan celebrates, above all, the island’s “Culture of Congestion.” Thirty years later, we’re so tired of congestion that we’re considering charging for it.