|

(Photo: Courtesy of The Artist and Metro Pictures) |

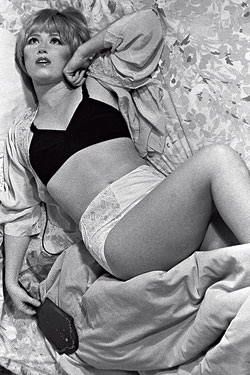

In the “Film Stills,” which you made between 1977 and 1980, you created a cast of women, all played by yourself, who seemed to be playing classic movie roles. How did the series start?

When I moved to New York, in the summer of ’77, I was trying to think of a new way to take pictures and tell a story. David Salle had been working at some sleazy magazine company where they had lots of shots of half-clothed women around, for those photo-novellas, like a cartoon but with photos. Slightly racy. It got me thinking, this cheap, throwaway image—if you just look at one, you make up your own story.

Why use yourself as a model?

I’d been using myself in my work, in costumes and as characters, so it was natural. I took one roll of film, and I had about six different setups of characters that were all supposed to be this one actress at various points in her career. In some she’s meant to look like the ingénue in her first role. In others she’s a little bit more haggard, trying to play a younger part. I purposely developed the film in hotter chemicals to make it crackle because I wanted it to look kind of bad and grainy.

Critics like to discuss the male gaze and the objectification of women in relation to your work. Did you think about that stuff?

I was totally unaware of that. In the late seventies, fresh out of college, I was trying to come to terms with my own ambivalence about liking to put makeup on but feeling, “Oh no, we have to be natural here, you’re not supposed to try and enhance anything.”

You must have liked dolls and dressing up as a child.

Dolls and making clothes and houses for them. And definitely dressing up. It was a guilty pleasure to invent these characters, because it allowed me to play around with makeup and the sexier, old-fashioned styles of dressing that I wouldn’t dare have worn.

I like the snazzy way you dress all the characters.

I was going to thrift stores and flea markets at first, just shopping for my own wardrobe and getting stuff cheaply. But then I’d find some amazing girdle or pointy bra that would flash back memories of my own childhood, of wearing a girdle at 13—when you certainly didn’t need one. But that’s what women did.

Did the scene around you have much influence on your work?

Back then, it was more the guys who were studio-visiting each other, and I wasn’t interested in that sort of male-bonding thing. And there weren’t that many other women artists who had discovered themselves. That was about to happen. But one interesting thing—there was much more crossover between different mediums. Robert Longo was in a band; Kim Gordon from Sonic Youth, she was an artist as well as starting to play music. Instead of just feeling, “Oh, we have to go to these galleries to see some art,” we would also be saying, “Oh, we have to go hear so-and-so perform,” or watch a movie at Max’s Kansas City.

How about the look of New York? Was that important?

The second year I lived in the city, I felt bored with shooting in my apartment, so I made these lists of outdoor scenes to look for. I’d throw together a couple of outfits and wigs in a suitcase, and my boyfriend at the time, Robert Longo, drove me around the city in his van and I’d say, “Oh, let’s stop here,” and I’d change in the van and then hand him the camera and hop out and get into position and kind of walk around and say, “Okay, now shoot me from here, try this angle.” I might start with a short blond wig and minimal makeup, and the next one I would change it to a black wig with more-severe makeup.

Did you invent private stories about the characters?

I created in my mind an idea of who the character was, if she’s wearing a certain outfit. Maybe the working girl on her way to her first job in the city. Something like that.

It’s hard to know what the characters are thinking.

I like characters who are not smiling—they’re sort of blank. It makes the viewer come up with the narrative.

When you look at them now, what do you see?

Sometimes I think about how much the city has changed. There were a bunch that were shot right around the World Trade Center, and along some decrepit buildings near the river that are gone now. I think also about, well, you know, sometimes I was doing this stuff on my way to my part-time job as a receptionist at a nonprofit art gallery. And sometimes I would stay in character. A couple of times I’d get dressed up and just go to work that way. When I had my first show, they said, “Well, why don’t you come to work once in a while in character?,” but I started to feel like I was not … well, in this city, it wasn’t a safe thing to do. I felt too insecure.

Why?

I guess because I was still intimidated, and I just felt like—

Like you were wearing a mask?

Like I wasn’t wearing my normal armor. I was vulnerable by being this other character. We’re all products of what we want to project to the world. Even people who don’t spend any time, or think they don’t, on preparing themselves for the world out there—I think that ultimately they have for their whole lives groomed themselves to be a certain way, to present a face to the world.

Is that troubling?

I wouldn’t think of it as troubling, but it’s definitely been an issue in my life—that even in relationships I was a kind of chameleon. Sometimes not to the best advantage.

But there’s a pleasure, too, in being a chameleon.

Definitely. And it’s useful sometimes.

What mistakes do people make about the “Film Stills”?

Referring to them as self-portraits.

What about those who call your work narcissistic?

I really don’t think that they are about me. It’s maybe about me maybe not wanting to be me and wanting to be all these other characters. Or at least try them on.