|

(Photo: Brad Harris) |

Although with regard to the past, when this is reported correctly what is brought out from the memory is not the events themselves (these are already past) but words conceived from the images of those events, which, in passing through the senses, have left as it were their footprints stamped upon the mind. My boyhood, for instance, which no longer exists, exists in time past, which no longer exists. But when I recollect the image of my boyhood and tell others about it, I am looking at this image in time present, because it still exists in my memory.

—St. Augustine of Hippo, Confessions, 398

Memory is the same as imagination.

—Giambattista Vico, New Science, 1725

NOTE: This profile of the allegedly fake memoirist Augusten Burroughs is based on real events. Dialogue has been compressed, and chronology has been changed for dramatic effect.

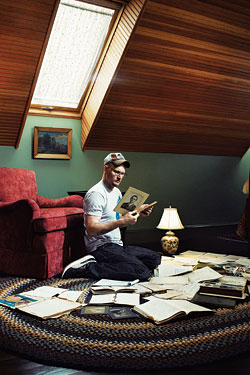

Augusten Burroughs travels between Amherst, Massachusetts, where he lives, and New York, where he keeps an apartment, in a hired black Town Car, so he can sit in the back and chew nicotine gum and watch Trauma: Life in the ER on his iPod. He has come down, this April afternoon, to walk me around his old neighborhood while I dredge his apparently superhuman memory in an effort to determine whether he is, as millions of readers seem to believe, one of the most honest men on the planet—someone willing to share unvarnished true-life details of his childhood statutory rape and the time he murdered a rat in cold blood in his bathtub—or whether, as others have alleged (some of them in a court of law), he is actually a gigantic liar. I know that his memory is superhuman because he told me so, last week, over lunch. “I can remember being 8 months old in my high chair,” he said, chewing nicotine gum between bites of a goat-cheese omelette. “I can remember learning to walk. I can remember the exact sound the wooden spoon made on the aluminum pot on the stove. I can remember that the lid of the pot had a little knob, putting it in my mouth like a nipple. I can remember my high chair’s tray: The metal was textured, it had peak-valley, peak-valley, peak-valley, a small design element, a striation.” Tomorrow he leaves for San Diego to give a speech to someone about something or other. He doesn’t remember. “I just show up and talk,” he says.

He does, indeed, show up and talk. In person, Burroughs has a focused analytical intelligence that doesn’t always come through in his writing, which tends to be emotional and therapeutic and often is written from the perspective of a child. In our first conversation, he gives me speeches about the neglected genius of middlebrow novelist Elizabeth Berg (“If she had a penis, she’d be John Updike”), the origins of southern manners among Belle Époque New York millionaires, and the ecstasy of quantum physics. (He’s particularly jazzed about a phenomenon called “entanglement,” in which photons at opposite ends of space seem to communicate instantaneously.) He says he can differentiate between the major brands of carbonated water (“Perrier has sharp, broken-glass bubbles; Calistoga’s are smaller”), as well as between real homeless people and college kids pretending to be homeless. “There’s that look you can’t replicate with eye shadow,” he says. He is, in person, almost the opposite of his textual persona: tall, athletic, and intense. In an effort not to look “pregnant” for the book tour for his new memoir, he’s been working out every day and recently broke his addiction to midnight bags of M&Ms. He is wearing, today, his publicity-tour uniform: jeans, black leather jacket, a blue T-shirt with some kind of Victorian woodcut on it, and a brown mesh trucker hat featuring an artsy cow. The biggest surprise, to me, is that he radiates trustworthiness: He seems open, unrushed, self-deprecating, and willing to discuss any subject with piercingly direct eye contact. He asks questions about my childhood, listens carefully to the answers, and follows up with more questions. He is unfailingly kind to waiters. His voice is dry, higher-pitched than I’d expected, and a little twangy, the product of growing up under highly educated southern parents in western Massachusetts. He puts an especially heavy accent on the word was: It comes out sounding like “wahz” or “waaaahz”—as if, even phonetically, the past requires disproportionate emphasis.

I find myself trusting Burroughs far more in person than I ever have in print—and yet I recognize in this trust yet another reason to doubt. Our meeting, after all, is just the first phase of a global marketing campaign whose success depends entirely on the spectacle of his honesty. Trust is the product for sale.