|

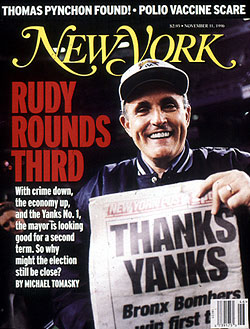

From the November 11, 1996 issue of New York Magazine.

Thomas Pynchon leaves his Manhattan apartment building; he's wearing a pair of jeans and comfortable shoes. He, of course, looks much older than his pictures; the last one anybody has ever seen was taken in 1955, when he was in the Navy. He'll be 60 next year, and his hair has gone gray. He keeps it long, and has a white mustache and beard. It appears that his famous snaggle of teeth has been fixed. He wears glasses. His eyes, shadowed in dark in those few early photographs, are blue. Thomas Pynchon walks down a New York City street in the middle of the morning. He has a light gait. He floats along. He looks canny and whimsical, like he'd be fun to talk to; but, of course, he's not talking. It's a drizzling day, and the writer doesn't have an umbrella. He's carrying his own shopping bag, a canvas tote like one of those giveaways from public radio. He makes a quick stop in a health-food store, buys some health foods. He leaves the store, but just outside, as if something had just occurred to him, he turns around slowly and walks to the window. Then, he peers in, frankly observing the person who may be observing him. It's raining harder now. He hurries home. For the past half-dozen years, Thomas Pynchon, the most famous literary recluse of our time, has been living openly in a city of 8 million people and going unnoticed, like the rest of us.

Ask people in Pynchon's own neighborhood where they think he might be hiding out, and you get a variety of responses: "He lives in Mexico," says a clerk in a bookstore a few blocks from his building.

"Out west somewhere," says a salesperson in a gourmet-coffee store around the corner.

"He's disappeared, and no one will ever find him, because that's how he wants it," says a man walking past the entrance to Pynchon's apartment building.

Since 1963, when Pynchon's first novel, V., came out, the writer—widely considered America's most important novelist since World War II—has become an almost mythical figure, a kind of cross between the Nutty Professor (Jerry Lewis's) and Caine in Kung Fu. There has never been a confirmed Pynchon sighting published before this one, but there have been plenty of wild theories about his whereabouts, advanced by gonzo fans and serious scholars. People have said that Thomas Pynchon is "really" J. D. Salinger; that he travels around by bus, crisscrossing the country and leaving little clues as to his identity; that he's posed as a literary-minded bag lady who writes letters to an obscure Northern California newspaper (there's a new book out about that, The Letters of Wanda Tinasky). There was even a rumor, hotly debated on the Pynchon Websites on the Internet, that Thomas Pynchon was the Unabomber. Pynchon showed up at an apple-picking fest in Northern California, calling himself Tom Pinecone; Pynchon was walking the Mason-Dixon line, researching his next book, said to be a "big one" (it's coming out, finally, in the spring of 1997, according to Pynchon's editor at Henry Holt). Sal Ivone, managing editor of Weekly World News—the tabloid that told the world that "Elvis is alive"—reports, "In the first week of October, Weekly World News recorded three Elvis sightings, two Bat Boy sightings, one Bigfoot encounter, and, amazingly, one for Thomas Pynchon. We haven't checked it out because it sounds too far-fetched to us."

In the seventies, after the startlingly brilliant and difficult Gravity's Rainbow—perhaps the least-read must-read in American history—came screaming across the landscape, Pynchon was hot, in mediagenic terms, and a virtual subgenre of New Journalism sprang up and circled around trying to find him, or at least understand him as a literary MIA. " 'My quest for Thomas Pynchon,' " says David Streitfeld, book critic for the Washington Post, "was fourteen gallons of indulgence: 'I started on my quest for Thomas Pynchon, and I found myself.' "

In 1990, when Pynchon's last novel, Vineland, appeared, there was again a spate of articles speculating on the location of the so-called Invisible Man. THOMAS PYNCHON, COME OUT, COME OUT, WHEREVER YOU ARE, shouted one magazine headline. People magazine called Pynchon's address "the best-kept secret in publishing."

On an openly accessible online service that uses a cross-referencing of credit-card and telephone numbers, New York discovered Thomas Pynchon's address in about ten minutes. "We have recently moved," Pynchon noted in his introduction to Slow Learner, a book of early short stories, "into an era when . . . everybody can share an inconceivably enormous amount of information, just by stroking a few keys on a terminal."