|

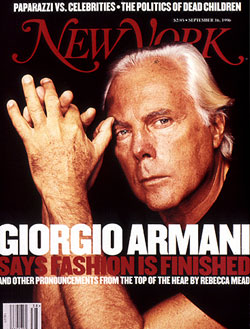

From the September 16, 1996 issue of New York Magazine.

Among the most exquisite of artworks in the city of Florence are the frescoes by Benozzo Gozzoli that decorate the walls of the chapel in the Medici-Riccardi palazzo, a place of worship so tiny that no more than fifteen people are permitted to enter at any one time. Gozzoli's purported subject matter is the Journey of the Magi: The three wise men, accompanied by scores of associates and retainers, process on horseback to pay homage to an unseen Jesus. But the actual subject of the frescoes is the glory of the Medici clan itself. Each figure on the walls has the face of this or that prince or nobleman, uncannily lifelike, gazing out at the onlooker. The chapel serves as a kind of fifteenth-century photograph album for the most influential family of the time, and even the Tuscan countryside—the dramatic, flowered hills through which the Magi ride—is depicted in glorious detail.

It was through those very hills outside Florence that, one Tuesday evening this July, another cavalcade of worthies ascended to pay their own kind of obeisance to contemporary power—not to a deity, but to a modern-day monarch of sorts: Giorgio Armani. During the few days prior, the men's collections had been taking place in Milan, but Armani had determined to show in Florence rather than at his Milan palazzo. So that morning, the fashion caravan—that odd assortment of journalists and store buyers who travel from capital to capital, determining the rise and fall of the hipster pant or the patent-leather shoe—had climbed aboard trains or piled into rental cars and journeyed 200 miles south. Here they had witnessed not a mere catwalk show but a spectacular 90-minute-long performance and tribute to Armani created by the avant-garde director and choreographer Robert Wilson, who had created within the Stazione Leopolda, a vast, abandoned railway station, a series of surreal, beautiful tableaux, all peopled with models and dancers wearing Armani. There was a summer beach scene through which dancers dressed in the spring-summer 1997 collection wandered; a glamorous evening party in which the women wore gowns from Armani's personal archive, which were in some cases as old as the bodies they hung from; a sculpture hall in which eight exquisitely muscled young men, barely dressed in swimwear, stood on podiums and affected the attitudes of sculptures, their hair whitened to connote marble, though it also bore a marked resemblance to Armani's own stark-white coif. And after the show, a select group of spectators—Eric Clapton, Lee Radziwill, press, and buyers, as well as assorted Florentine bigwigs—were ushered into minibuses to ascend the dark hills above the Arno for a party in Armani's honor, held on the candlelit terrace of a seventeenth-century villa.

They came bearing, if not incense and myrrh, then rich congratulations, even those who afterward admitted being bemused by the Wilson extravaganza and unable to focus on what was, after all, merchandise. ("I went to Florence to see the clothes, and I was a little disappointed that I didn't see the clothes," Kal Ruttenstein of Bloomingdale's said later. "But I am sure it was beautiful: Everybody said it was beautiful, and fabulous-looking people said how beautiful it was, so I guess it was beautiful.") Armani moved among his guests, speaking Italian to those who spoke Italian, French to those who didn't, his manner one of quiet command. He wore a tight blue T-shirt and slim, tailored pants; he was, as usual, jacketless. With his deep tan and incongruously unlined face, his clear blue eyes, his impeccable limestone-white hair, his muscled arms and trim torso, Armani's very person seemed to be fashioned from fabrics richer than those available to simpler, poorer folk.

For all the production values, though, it turned out to be a low-key evening, a party for people who are really too busy to party. The next morning, the fashion caravan was due to move on to Paris for that city's men's shows; the following week, it would shift en masse to New York, for the American collections. Long before dinner was served, the guests were comparing travel itineraries and declaring intentions to get to Florence's minimal airport early enough to beat the crowds and, by implication, one another. Everyone was too busy wondering how to get back down to the city to enjoy being out of it. Armani himself slipped out before many of the guests had cleared, his social duties performed. Like those of the members of the fashion caravan, his thoughts were, presumably, already on what was to come next. The party was an essential display of power, but that power—the energy of a $1.7 billion business—takes more than late nights and glad-handing to sustain it.