|

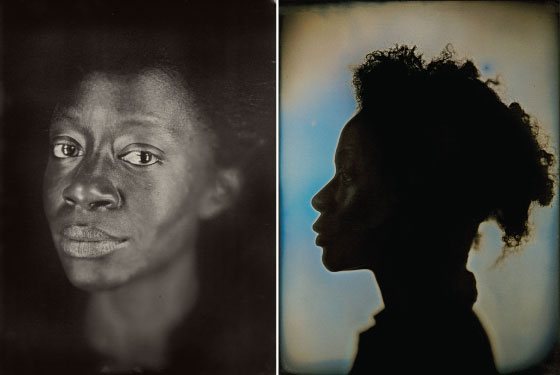

(Photo: Daguerreotypes by Chuck Close./Jerry Spagnoli Studio Inc. ) |

Sometimes it worries me that I have an imagination like I do,” says Kara Walker. It’s an imagination that, in its tirelessly inventive, self-immolating wickedness, has drawn the 37-year-old artist comparisons to both Goya and Richard Pryor. Walker has repurposed a fusty Victorian art form—the silhouette—as a medium for the depiction of the most graphic abuses and transgressions (rapes and lynchings), perpetrated in the most profoundly racist of power dynamics (slave masters and pickaninnies). Cut-paper and shadow puppets, those innocuous grade-school crafts, become explosive devices in her hands.

The Whitney show will be Walker’s first full-scale American museum survey, but last year she organized the timely and affecting “After the Deluge” at the Metropolitan Museum. Plans for a special project at the Met were already under way when Katrina struck. “I recognized suddenly that I could use the Met to talk about this weird confluence of history, mythology, and on-the-ground pain,” says Walker. Combining her own work with art from the museum’s collection, the exhibition made old European paintings of floods and disasters at sea look shockingly contemporary, in the same way that the Superdome resembled nothing so much as a marooned slave ship. The show also reminded people that Walker’s art has always been steeped in the fetid swamps of the antebellum South—in, as she memorably put it, “the story of Muck.”

Some people would prefer that she not get her hands dirty. A decade ago, after Walker won the MacArthur award, the septuagenarian African-American artist Betye Saar launched a massive letter-writing campaign calling Walker’s work “sexist and derogatory” and the artist “young and foolish.” That conversation hasn’t so much died, says Walker, as seeped into other cultural arenas. “There was a protest in front of the Virgin Records store the other day,” she recalls, “about musicians using words and phrases demeaning to women, blacks… Artists and musicians have to be able to maintain that weird, nauseating line between excess and personal shame.”

Shame on us, Walker’s work seems to say, but also shame on me. “It wouldn’t feel right,” she says, “if I were just snubbing my nose at the viewer … if I weren’t part of this weird act of making and looking—and reeling.”