|

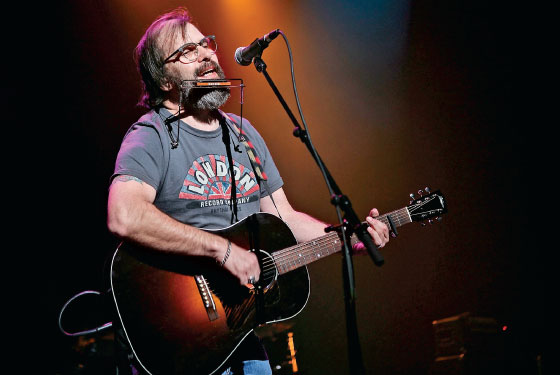

(Photo: Scott Gries/Getty Images) |

‘I’m too fuckin’ old to live in Williamsburg,” says Steve Earle. “I didn’t wait to move here until I was 50 so I could live in Brooklyn.”

Earle is a Nashville legend; his 1986 debut, Guitar Town, was the rallying cry for a generation of rebellious “new-country” artists, and he stayed on as their hard-living figurehead. But two years ago, Earle gave in to a longtime fantasy and moved to the West Village. His love affair with his new hometown is documented on his forthcoming album, Washington Square Serenade; the opening track, “Tennessee Blues,” makes Earle’s new allegiance clear. “Bound for New York City and I won’t be back no more,” he sings. “Boys won’t see me around—good-bye, guitar town.”

The album’s shimmering mix of acoustic guitars and supple beats was provided by producer John King, half of the Dust Brothers team that has worked with Beck and the Beastie Boys. “I wanted to make a folk record arrived at by hip-hop rules,” says Earle. The subject matter also represents a shift, away from the overt politics that has defined Earle’s recent work; he’s perhaps best known for 2002’s “John Walker’s Blues,” his sympathetic study of John Walker Lindh, the “American Taliban.”

“I knew this was gonna be a more personal record,” he says. “It’s not an apolitical record, but it’s also somebody else’s turn. I can’t do that all my life.” He adds that after his 2005 marriage to singer Allison Moorer—his seventh, including two go-rounds with the same woman—“love songs were pretty hard to avoid.”

As his matrimonial history might indicate, it hasn’t been an easy road for Earle. In the past, he’s battled a heroin addiction—“I bought a lot of dope there,” he says about the East Village. “I was banned from 7A for being a junkie”—and in the mid-nineties, he wound up in jail on drugs and firearms charges.

Since being paroled in 1994, though, he has been on a creative tear. In addition to releasing almost an album a year, Earle has worked as an actor, with a role on The Wire (“I play a redneck, recovering addict,” he says. “That’s not acting”); a radio host for Sirius; a fiction writer (Doghouse Roses, a 2002 collection of stories; he’s also at work on a novel); a playwright (Karla, about Karla Faye Tucker, who in 1998 was the first woman executed by the state of Texas since the Civil War); and a progressive political activist, often focusing on protesting the death penalty.

You might expect that Earle would chafe at the gentrification that has engulfed the city, particularly his own newly adopted neighborhood, but it doesn’t bother him so much. The Village has “always been a tourist trap,” he says. More important is its blend of bohemians and students, which provided the spark for the sixties folk boom that remains close to the heart of his music. “That’s the point at which rock and roll becomes art, and certainly when it becomes anything resembling literature,” he says. “So I’m living where my job was invented. I mean, how lucky am I?”