|

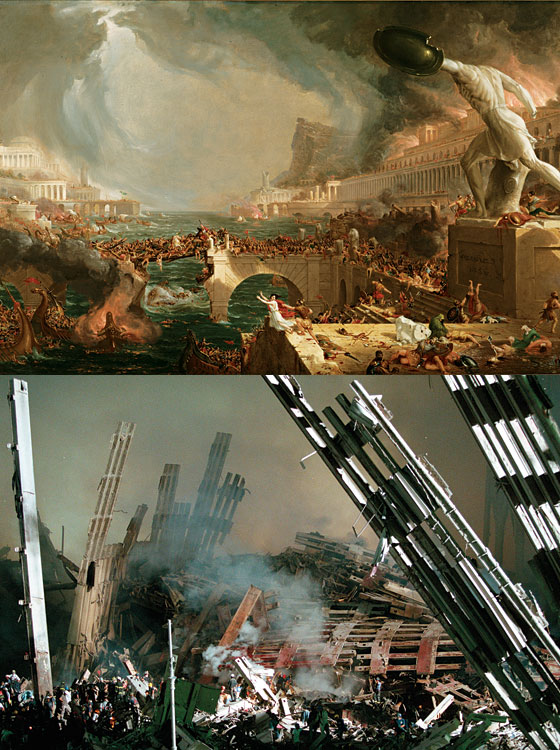

Top: Thomas Cole, The Course of

Empire: Destruction, 1836.

Below: A photograph of the aftermath of the attacks, September 2001. (Photo: Collection of the New-York Historical Society (top); Timothy Fadek/Polaris (bottom)) |

The urge to grandstand is human: Sometimes you feel you just have to wreck people’s self-serving illusions. Have a knockdown, drag-out. Nuke ’em. All in a good cause, you think: Moral rectitude—the truth—requires rhetorical violence. I know because I’ve done my share. In the immediate aftermath of 9/11, apocalyptic grandstanding was basically all I did. Despite being until then your standard-issue California-dwelling, left-leaning feminist academic (sort of)—an English professor—I suddenly found myself delivering bellicose right-wing tirades. Monster-blasts of aggression, vengefulness, and rage. Big mean tough talk of exactly the sort I’d previously despised and associated with the most reactionary (and stupid) politicians and talk-show hosts.

The stakes were pitifully low: Most of this fulminating went on in private. Or close enough to it. I was 3,000 miles away when the attacks occurred—indeed, comfortably ensconced at home in sunny, late-summer San Francisco. But when I had to give a lecture at a British university not long after, my mental and emotional chaos did not deter me from making a host of fairly wild impromptu remarks about them, including the statement—delivered with rictus-face and mad gleam—that had I somehow been given an opportunity in advance of the attacks to obliterate Mohamed Atta and his wretched associates, I would have happily done so. I want to kill them! Fucking thugs. The poor students looked frightened and stupefied.

Similar feelings burst forth when an editor in London at a left-wing literary magazine for which I sometimes wrote—we were having lunch—asked why Americans were so stunned by 9/11. Couldn’t any thinking person see that foolish U.S. policies in the Middle East had helped precipitate the attack? I started fuming incoherently about the Houses of Parliament being blown up—thousands of people killed, etc.—while he looked on, baffled. I squeaked on undaunted: If the U.S. hadn’t won the Cold War, London and Paris would now look like Kiev and Smolensk! You guys owe it to us! Hardly the charming lunch guest. In a matter of days, I’d morphed into a sort of cockeyed Otto von Bismarck crossed with the Ancient Mariner: a weird, caved-in convert to some of the very oldest of the old ideas—all the sad, abject, bloodshot human theorems. An eye for an eye and—you know the rest.

But everybody was saying crazy things then. Witness the venerable German composer, Karlheinz Stockhausen, whose shocking remarks at a press conference at a music festival in Hamburg six days after the attacks made headlines. The events of 9/11, he’d enthused, were “the greatest work of art imaginable for the whole cosmos.” Things had gone from bad to worse to incendiary when, like Batman’s Joker, he warmed to his theme: “Minds achieving something in an act that we couldn’t even dream of in music, people rehearsing like mad for ten years, preparing fanatically for a concert, and then dying; just imagine what happened there. You have people who are that focused on a performance and then 5,000 people are dispatched to the afterlife, in a single moment. I couldn’t do that. By comparison, we composers are nothing.”

Stockhausen’s comments produced immediate repugnance worldwide. “To the victims of terrorism,” wrote a commentator for the Frankfurt Allgemeine Zeitung, the composer’s “mental descent into hell … must seem like hideous mockery.” Although Stockhausen subsequently claimed he had been misunderstood [S4], he became a pariah for a while in Europe and North America. His concerts at the music festival were canceled; his daughter, a pianist, said she would no longer perform using the Stockhausen name. When he died, in 2007, many obituarists mentioned the 9/11 scandal; indeed, for some, it overshadowed his extraordinary musical career.

Though a microblip on the scale of things, Stockhausen’s remarks have stayed with me, no doubt because—even after ten years and the inevitable flattening out of one’s 9/11 memories—I can’t decide what I think about them. At the time his comments struck me as loony and repellent, and I was inclined to dismiss them—yes—as grandstanding. Intellectual grandstanding, that is—of a sort I’d seen exhibited by fellow humanities professors at rich universities across the U.S., who despite tenure and plush middle-class lives thought of themselves as Marxists or somehow on the academic left. September 11 had provided them yet another opportunity to reiterate the logic of the dialectic—how you couldn’t really blame the jihadists, because, as Gramsci said … , etc. Happily, few regular people paid any notice or were even aware of these momentous “interventions” emanating from the ivory tower.

But that was how it was after 9/11: Everyone (again, I include myself) wanted to wound everyone else, with words if not weapons. We were all impossibly confused and frightened—like terrified children, really—and otherwise sensible adults reverted to whatever ego defenses they had evolved over a lifetime to ward off feelings of humiliation, panic, and despair. Stockhausen, the Marxists, I myself, we all were doing it. The posturing. Pretending to be intellectual and above it all. Together we’d been dealt an unthinkable blow: Let the railing begin.