|

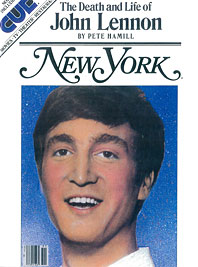

*From the December 20, 1980 issue of New York Magazine.

1. I READ THE NEWS TODAY (OH BOY)

Well nobody came to bug us,

Hustle us or shove us

So we decided to make it our home

If the Man wants to shove us out

We gonna jump and shout

The Statue of Liberty said, “Come!”

New York City . . . New York City . . .

New York City . . .

Que pasa, New York?

Que pasa, New York?

—John Lennon, 1972*

The news arrived like fragment of some forgotten ritual. First a flash on television, interrupting the tail end of a football game. Then the telephones ringing, back and forth across the city, and then another bulletin, with more details, and then more phone calls from around the country, from friends, from kids with stunned voices, and then the dials being flipped from channel to channel while WINS played on the radio. And yes: It was true. Yes: Somebody had murdered John Lennon.

And because it was John Lennon, and because it was a man with a gun, we fell back into the ritual. If you were there for the sixties, the ritual was part of your life. You went through it for John F. Kennedy and for Martin Luther King, for Malcolm X and for Robert Kennedy. The earth shook, and then grief was slowly handled by plunging into newspapers and television shows. We knew there would be days of cliché-ridden expressions of shock from the politicians; tearful shots of mourning crowds; obscene invasions of the privacy of The Widow; calls for gun control; apocalyptic declarations about the sickness of America; and then, finally, the orgy over, everybody would go on with their lives.

Except . . . this time there was a difference. Somebody murdered John Lennon. Not a politician. Not a man whose abstract ideas could send people to wars, or bring them home; not someone who could marshal millions of human beings in the name of justice; not some actor on the stage of history. This time, someone had crawled out of a dark place, lifted a gun, and killed an artist. This was something new. The ritual was the same, the liturgy as stale as ever, but the object of attack was a man who had made art. This time the ruined body belonged to someone who had made us laugh, who had taught young people how to feel, who had helped change and shape an entire generation, from inside out. This time someone had murdered a song.

And it had happened in a city to which that artist had come in order to be private, in order to be safe. It had happened in New York.

¿Qué pasa, New York?

2. IMAGINE ALL THE PEOPLE

If you had the luck of the Irish,

You’d be sorry and wish you were dead. . . .

—Lennon and Ono, 1972

So we all went to the Dakota. We had nowhere else to go. Yes: If you’ve been trained as a reporter, you’re supposed to go places with a cold eye. But I’m sorry; even as the flood tide of rage receded, the cold eye wasn’t possible. Not for John Lennon. Our lives had intersected at critical moments since the winter of 1963, that bitter season after Dallas when people my age realized that they would never again be young. We met in London, in an upstairs joint called the Ad Lib. I was with Al Aronowitz. Ringo and Paul were there too, and later the Stones came in, and we were all at a big table, with music pounding, and girls crowding around, and Brian Jones all blond and small getting drunk on whiskey in a pool of solitude. John Lennon came in after a while with Brian Epstein and sat down next to me. Aronowitz was telling them they had to listen to Dylan, and McCartney was nodding, agreeing with Aronowitz, while Mick Jagger got up to dance with a young blonde wearing too much makeup.

“To hell with Dylan,” Lennon said. “We play rock ’n’ roll.”

“No, John, listen to him,” Aronowitz said. “He’s rock ’n’ roll too. He’s where rock ’n’ roll’s gonna go. Listen.”

Lennon’s mouth became a tight slit, “Dylan, Dylan. Give me Chuck Berry, Give me Little Richard. Don’t give me fancy crap. Crap, American folky intellectual crap. It’s crap.”

He was snarling and bitter and hard. He didn’t want to talk about music. He didn’t want to talk about writing. He looked down the table at Keith Richard. “What the hell are the Yanks here for?” he said, Richard smiled and shrugged. McCartney reached over and touched John’s hand. “Ach, come off it, John,” he said. Lennon pulled his hand away and turned to me.