|

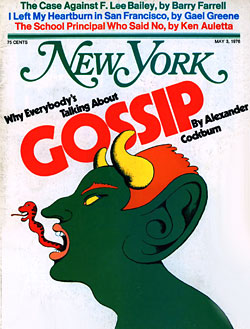

From the May 3, 1976 issue of New York Magazine.

"Never lose your sense of the superficial" was the peremptory advice once given his editors by Lord Northcliffe, the founder of modern popular journalism. They've been following his advice in England, more or less, ever since. In the United States, on the other hand, where journalists have a higher view of their calling, it looked for a while as though seriousness and deep purpose were carrying all before them: reporters discarded the brashness of The Front Page for the solemnity of All the President's Men. But all is not lost. It's become evident over the last few months that more and more members of the Fourth Estate are recollecting the essential meaning of their trade, which is to discover the inconsequential and get it into print.

The spirit of triviality lurking in the bosom of the average newspaper reader will never be quenched, and is indeed now blazing up more fiercely than ever before. For a decade the dark clouds of the Vietnam war, of Watergate, of the recession, seemed to obscure the landscape. Now, with a "recovery," with the placid realities of structural unemployment and the prospect of a more or less steady run to the grave under either a Republican or a Democratic president, it is plain that what a large section of the literate citizenry is after is plenty of rousing chatter about other people. Gossip, in fact, has crawled out from under its stone and is now capering about in the full light of day.

There are, of course, problems with the word itself. In old thrillers the villain, advancing on the pinioned hero with whip and thumbscrew, used to say suavely, "Not torture, my friend. Shall we just call it . . . persuasion?" Something of the same coyness now seems to envelop the notion of gossip

Readers, hurrying home from the supermarket with copies of People, the National Enquirer, and the Star, tell you that they are just out for entertainment; reporters, bearing down on their victims, say they are after the facts; editors, with all due primness, tell you the public is now interested in personalities, and given half a chance will throw in a short lecture on the passing of the issue-oriented sixties. The truth of the matter is that they are all chasing after gossip, but like the old villain are too polite or are as yet unprepared to call the thing by its proper name.

"Gossip?" says Richard Stolley, managing editor of People. "We have expunged that word from our vocabulary. The term has held connotations of untruthfulness. If we're asked to describe what we are doing we prefer to call it 'personality journalism' or 'intimate reporting.'" That's awfully nice for Stolley, perched atop a circulation for People which is now reaching 1.8 million. I hope he sleeps the better for having the notion of "personality journalism" tucked under his pillow. Readers, scurrying out to buy last week's edition of his magazine, which has on its cover the words BARBRA STREISAND: FOR THE FIRST TIME, SHE TALKS ABOUT HER LOVER, HER POWER, HER FUTURE, presumably have a rather more zestful outlook on the situation.

Stolley is right, of course, in saying that the word "gossip" does have louche undertones. It is one stage nastier than "chatter," one stage seedier than "investigation." It's poised between rumor and the real, between the stab in the back and the handshake, between tastelessness and the libel lawyer's office. True gossip is only barely fit to print, is the rank underbelly of journalism. In the words of James Brady, vice-chairman of the Star, gossip is difficult if not impossible to confirm, but contains the elements of an accurate story. Gossip, in short, is nasty.

People magazine is right at the top of the ladder between decency and outrage. We find it near heaven along with the sedate chatter in the New York Times's "Notes on People" section. A little below, we find "People" in the Washington Post "Style" section. Then down we go, past Suzy, Maxine Cheshire, Liz Smith, Herb Caen, Sid Skol-sky, Earl Wilson, WWD, Interview, "The Ear" in the Washington Post, Sally Quinn, Ben Bradlee's memoirs, Rona Barrett, Cindy Adams, down, down into the caverns of the Star and the National Enquirer where spectral images of Jacqueline Onassis, Elizabeth Taylor, and Princess Margaret shriek for release from their eternal torment—a torment, incidentally, from which the entirely fictional French gossip sheet France Dimanche has just liberated Princess Margaret, since its headline recently announced LE SUICIDE DE LA PRINCESSE MARGARET.

In the pantheon of gossip it's becoming clear that a certain shift in personnel is occurring. Jostling in among film stars, royalty, and international refuse of every description have come "media stars" and, increasingly, politicians. A certain widening of gossip's focus is in fact taking place.