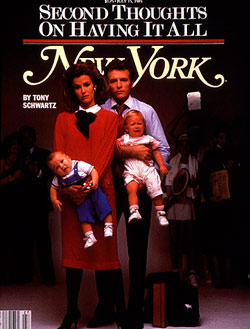

From the July 15, 1985 issue of New York Magazine.

|

Twice during the past month, colleagues approached 38-year-old Rebecca Murray* and volunteered identical assessments of her life: "You are the woman who has everything," they told her. The notion staggered Rebecca. "I have never, ever thought of myself that way," she says. But it's not hard to see what her co-workers had in mind.

For the past eighteen years, Rebecca has been married to the same man—Robert, now 42—and their marriage remains strong. Their five-year-old daughter is pretty and bright. Rebecca works as a records manager for a large financial institution and earns $40,000 a year—with plenty of potential to move up. Robert makes $43,000 a year as the business manager for a publishing house. Free-lance writing brings in another $5,000 a year. He is a novelist, and although his advances have been small so far, that could change with a single success. The Murrays' combined income of nearly $90,000 is more than four times the salary earned last year by Robert's father, a construction supervisor in Florida, and a lot of money by nearly any standard. What's more, they pay just $450 a month for a rent-stabilized apartment on a pretty street on the Upper West Side. Among other things, they can afford the $8,500 a year it costs to send their daughter to a private day-care center where the ratio of children to teachers is four to one.

But none of this compensates for what Rebecca feels is missing in her life. "Time," she says. "I don't have enough time for my child, I don't have enough time for myself, and I never have enough time for my husband. He gets whatever I have left at the end of each day, and usually that's nothing. I don't want to leave my child in the mornings—and she doesn't want me to go. I'm fine once I get to work, but once the day starts winding down, I get very anxious to rush to my kid. I can't wait, I want to be there in a second, and sometimes the subway is interminable. At the same time, I'm aware that I'm looking at an evening that's not going to be relaxing. Realistically, I'm facing three more hours of work—the child care—and I've already put in a full day at the office."

Rebecca reached her breaking point on a subway during rush hour last summer. "I was standing on this miserable, crowded, hot train," she remembers, "coming from a job that doesn't give me all that much pleasure, to pick up my child, who'd been away from me the whole day, to go home to an apartment so small that my husband and I sleep in the living room on a futon mattress." That night, Rebecca made a decision. "There's such a thing as quality of life," she told her husband, "and this isn't it."

Robert was inclined to agree. Although he'd vowed never to leave New York City, the birth of his daughter changed his mind. He worried that they were running harder just to stay in place. While they are scarcely materialistic—the Murrays almost never take vacations, rarely go out for dinner, and spend little on clothes—Robert found they barely met their expenses. "It's been possible for us to get by with a certain amount of comfort," he says, "but it hasn't been possible to accumulate anything, to create a safety net, or even to afford a decent-size living space."

Last fall, the Murrays began looking for houses outside the city. High prices drove them from Ridgewood, New Jersey, through Bergen County, up to Rockland, and finally into Orange County. They were determined to buy a house with space for a sum they could afford. In December, using a small inheritance, they put down $30,000 on a $90,000 house in Orange County and took out a mortgage for the remaining $60,000. Because they chose a town that was considered slightly beyond commuting distance and was largely undiscovered as a vacation retreat, the Murrays got a lot of house for their money: ten rooms overlooking a lake, just an hour and a half by car from midtown Manhattan.

But even then, the Murrays resisted moving there full-time; the change seemed too radical. Finally, driven by the need to settle on a kindergarten for their child, they made their decision last month. Rebecca gave notice at her job, and in August, after living for two decades in Manhattan, the Murrays will move to a blue-collar town in upstate New York with a population of under 10,000.

Rebecca and Robert are exhilarated by the prospect of more space and less stress. The new house also means they can consider having a second child, something they've put off while living in a three-room apartment. On the other hand, the move means that Robert now faces at least three hours of commuting each day; he finds that in itself oppressive. It also means less time for his child, his wife, and his writing. For Rebecca, the move means an uncertain employment future as well as adjustments to life in a small town. The Murrays do not yet own a car, and Rebecca doesn't even know how to drive.