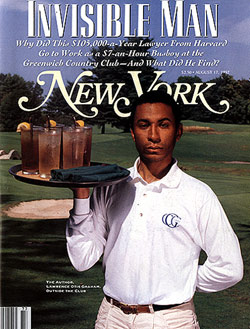

From the August 17, 1992 issue of New York Magazine.

|

I drive up the winding lane past a long stone wall and beneath an archway of 60-feet maples. At one bend of the drive, a freshly clipped lawn and a trail of yellow daffodils slope gently up to the four-pillared portico of a white Georgian colonial. The building's six huge chimneys, the two wings with slate-gray shutters, and the white-brick façade loom over a luxuriant golf course. Before me stands the 100-year-old Greenwich Country Club—the country club—in the affluent, patrician, and very white town of Greenwich, Connecticut, where there are eight clubs for 59,000 people.

I'm a 30-year-old corporate lawyer at a midtown Manhattan firm, and I make $105,000 a year. I'm a graduate of Princeton University (1983) and Harvard Law School (1988), and I've written eleven nonfiction books. Although these might seem like good credentials, they're not the ones that brought me here. Quite frankly, I got into this country club the only way that a black man like me could—as a $7-an-hour busboy.

After seeing dozens of news stories about Dan Quayle, Billy Graham, Ross Perot, and others who either belonged to or frequented white country clubs, I decided to find out what things were really like at a club where I saw no black members.

I remember stepping up to the pool at a country club when I was 10 and setting off a chain reaction: Several irate parents dragged their children out of the water and fled. Back then, in 1972, I saw these clubs only as a place where families socialized. I grew up in an affluent white neighborhood in Westchester, and all my playmates and neighbors belonged somewhere. Across the street, my best friend introduced me to the Westchester Country Club before he left for Groton and Yale. My teenage tennis partner from Scarsdale introduced me to the Beach Point Club on weekends before he left for Harvard. The family next door belonged to the Scarsdale Golf Club. In my crowd, the question wasn't "Do you belong?" It was "Where?"

My grandparents owned a Memphis trucking firm, and as far back as I can remember, our family was well off and we had little trouble fitting in—even though I was the only black kid on the high-school tennis team, the only one in the orchestra, the only one in my Roman Catholic confirmation class.

Today, I'm back where I started—on a street of five- and six-bedroom colonials with expensive cars, and neighbors who all belong somewhere. As a young lawyer, I realize that these clubs are where business people network, where lawyers and investment bankers meet potential clients and arrange deals. How many clients and deals am I going to line up on the asphalt parking lot of my local public tennis courts?

I am not ashamed to admit that I one day want to be a partner and a part of this network. When I talk to my black lawyer or investment-banker friends or my wife, a brilliant black woman who has degrees from Harvard College, law school, and business school, I learn that our white counterparts are being accepted by dozens of these elite institutions. So why shouldn't we—especially when we have the same ambitions, social graces, credentials, and salaries?

My black Ivy League friends and I talk about black company vice-presidents who have to beg white subordinates to invite them out for golf or tennis. We talk about the club in Westchester that rejected black Scarsdale resident and millionaire magazine publisher Earl Graves, who sits on Fortune 500 boards, owns a Pepsi-distribution franchise, raised three bright Ivy League children, and holds prestigious honorary degrees. We talk about all the clubs that face a scandal and then run out to sign up one quiet, deferential black man who will remove the taint and deflect further scrutiny.

I wanted some answers. I knew I could never be treated as an equal at this Greenwich oasis—a place so insular that the word Negro is still used in conversation. But I figured I could get close enough to understand what these people were thinking and why country clubs were so set on excluding people like me.

March 28 to April 7, 1992

I invented a completely new résumé for myself. I erased Harvard, Princeton, and my upper-middle-class suburban childhood from my life. So that I'd have to account for fewer years, I made myself seven years younger—an innocent 23. I used my real name and made myself a graduate of the same high school. Since it was ludicrous to pretend I was from "the streets," I decided to become a sophomore-year dropout from Tufts University, a midsize college in suburban Boston. My years at nearby Harvard had given me enough knowledge about the school to pull it off. I contacted some older friends who owned large companies and restaurants in the Boston and New York areas and asked them to serve as references. I was already on a leave of absence from my law firm to work on a book.