|

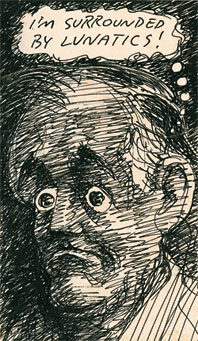

Illustration by Edward Sorel, 1976

|

The main reason that most city magazines suck, and have always sucked, is that their founders misapprehended Clay Felker’s biggest Big Idea. The brilliant germ of this magazine, when Felker launched it in 1968, wasn’t the duh geographical idea, covering a particular set of Zip Codes stylishly and colorfully on glossy paper. Rather, New York’s central subject has always been our local pageant of ambition, the yearning and hustling and jostling for power and—even more—status. The magazine was conceived as a kind of gleeful, fervid, useful weekly chronicle of social and cultural anthropology, descriptive (such as Tom Wolfe’s premiere-issue taxonomy of local accents, “Honks” versus “Wonks”) but also prescriptive (the grooviest merchandise and experience and art to ogle or buy).

Smart, knowing, slightly acid depictions of New York swells were not an entirely new periodical-journalism form. Around 1850, John Jacob Astor’s grandson published a magazine series on his fellow members of “The Upper Ten Thousand,” and The New Yorker in the twenties and thirties was up to something similar—but no one had ever done it quite so brazenly or consistently as Felker.

When I learned that his father ran The Sporting News, and that young Clay’s first magazine jobs were covering sports for Life and working with the team that created Sports Illustrated, I had an aha moment: His founding inspiration was to cover the scrum and spectacle of urban life as if it were sport of the most interesting possible kind, the city (or anyway the lower two-thirds of Manhattan) as postmodern gladiatorial coliseum, complete with colorful play-by-play and the latest stats and rankings.

This is not just some after-the-fact conceit about Felker’s vision. Thirty years ago, not long before his fellow owners and Rupert Murdoch squeezed him out of the magazine he had founded, Felker defined New York very simply as a guide to “how the power game is played, and who are the winners.” And Wolfe, his early superstar, has said that “Clay’s real interest, although I’m not sure he ever thought it out conceptually, was status and how it operates in New York. ... In New York Magazine, Clay really wrote an enormous novel about the city. ... It was his vision, his plot—a huge novel called The City of Ambition.”

One of the reasons this template can work well in New York City is that there are so many different high-profile, major-league “power games” being played here simultaneously. Whereas Los Angeles and Washington, D.C., are, for the kinds of people who read city magazines, one-industry towns, each with a single, consolidated, relatively unambiguous pecking order. New York, on the other hand, was and is the undisputed national epicenter of no fewer than seven glamour businesses—finance, news media, advertising, book publishing, theater, fashion, and fine art, with serious players in TV, music, and the movies on the field as well. Each one of those professional realms has its own complicated dynamic and etiquette and greasy poles, each with its own set of players perpetually scrambling up, sliding down, or holding on for dear life. Which means endlessly fresh material for journalism, as well as a critical mass of readers both fevering to read dissections and affirmations of their own professions’ tyros and machers and monsters, and also passingly curious about the big-timers and up-and-comers in the other games in town. (And about crime, a journalistic mainstay that was suddenly, wildly rife as Felker was inventing his serious but sensational magazine: Murders in the city increased by more than 50 percent between 1966 and 1968.) New York was made for New York, but also vice versa.

In his essay “Here Is New York,” E. B. White wrote of the three overlapping New Yorks, the most vibrant and important being “the New York of the person who was born somewhere else and came to New York in quest of something.” It’s no coincidence that White’s great venue, The New Yorker, was founded (in the twenties, at a thrilling, vertiginous, unsustainably go-go moment for the city and nation) by an editor reared in Colorado and Utah, just as New York was founded (in the sixties, the next great thrilling, vertiginous, unsustainably go-go moment for the city and nation) by a man who grew up in Webster Groves, Missouri.

For hyperambitious provincials like Harold Ross and Clay Felker, the impulse and ability to deconstruct this city’s life entertainingly was a result of their outsiders’ unjaded shock and awe at the spectacle, their clarity of vision. What people born and raised here understand intuitively and tend to take for granted—the precise paths to glory, the unspoken demarcations of power and status—are secrets that an émigré must puzzle out for himself when he arrives from the sticks. Probably all outsiders (if they are, in White’s genius phrase, “willing to be lucky”) mentally compile a New York City field guide and playbook when they’re in their twenties and thirties, but Felker did so literally, and published it in weekly serial form.