|

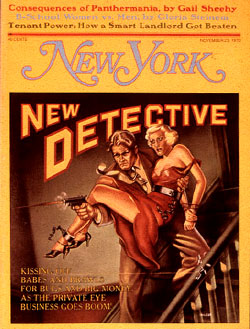

From the November 23, 1970 issue of New York Magazine.

A whimpering, tortured, dull-witted black was led into a Connecticut bog last year and there took a bullet in his head. Implicated in his death was Bobby Seale, chairman of the Black Panther Party, who is scheduled to stand trial this week in New Haven. In this second of a two-part series, Miss Sheehy examines the onset and the pathology of the revolutionary fever—and the paranoia—that gripped the Panther movement and led directly to the destruction of the party in Connecticut and nationwide raids, trials and more deaths.

New Haven, the Model City. New Haven, bellwether for the nation in urban redevelopment. New Haven, where poor black folks sat quiet on their porches while white liberals spoke for them and black bourgeois families walked in a flank to the white pocket-book Congregational Church and where the brush fires of black militancy—thanks to God and Yale—were banked and under control. So went the propaganda as America's war on urban blight bumbled through the sixties.

Warren Kimbro was a good black burgher of New Haven. Until 1969, when he caught revolutionary fever—Panthermania—and killed a man, Warren Kimbro was in the black middle.

Imagine, now—to catch the schizoid pull on Warren Kimbro over the past ten years—that you are standing with one foot in each of New Haven's two worlds:

One foot is on Yale Green. You are in the castle garden encircled by garret tops and gargoyles leaping off the turrets of a great university. Mighty gates curl back benevolently, beckoning . . . yes, you . . . into courtyards of autonomous Oxonian colleges. (But you are dark-skinned and never finished high school.) The people all around are young and vanilla with raspberry cheeks and the tell-tale moles of high breeding.

The other foot is in Congoland. In the bathroom of a rooming house. This is one of the shooting galleries along Congress Avenue and you are chipping a little heroin under the skin of your knee. It doesn't show there.

Congoland is a wedge of streets which form the core of New Haven's seven inner-city neighborhoods. It is near Yale. But on each of these corners the brothers of college age, unemployed, stand around in little clots, their young muscles bumping up through short-sleeved shirts, with nothing to do but rap. And rap some more, or hustle, or sip a little vodka, or shoot. Across the street from the shooting gallery sags an apartment house, long ago condemned by the Redevelopment Agency. Paste-ups of old Panther newspapers hang off its brick face. Like dead skin off sunburn. The famous Bobby Seale cover is there. You would recognize it as the drawing made of Chairman Seale being transported from the Chicago conspiracy trial to the New Haven murder trial. Bobby is strapped into an electric chair. His eyes bulge over the headline: THE FASCISTS HAVE ALREADY DECIDED IN ADVANCE TO MURDER CHAIRMAN BOBBY SEALE IN THE ELECTRIC CHAIR But you are too busy to absorb local color. Police have these shooting galleries staked out. You keep one eye on the exit. This is a constant about being black. It goes for the "distinguished colored gentleman" who serves at Yale club tables as well as the addict. One eye must always be kept on the exit.

Warren Kimbro passed 36 years picking his way between these two extremes. For the well-behaved Negro he was right on schedule.

Quit high school to follow his brother into the Air Force. Came out of the service in 1956—two years after the Supreme Court insisted, finally, on integrated schools. But Warren was already 22 and running on the old black schedule. Not quite certain what could be done with his life. His assets were small: a handsome face, gentle eyes, evangelical urges and the GI Bill. He was also wiry and tense, but not one to complain out loud. Warren trained as a clothes spotter. That put him in the dry cleaning business for the next six years. Still on schedule, he switched to making pastries in the Hostess cupcake factory.

"There was no colored, I mean, no black foremen of that time," recalls a black co-worker, Jerry Nelson. "Warren's function was, he was a fruitmaker. Like me. The first community activity Warren got involved in was Residential Youth Center. That wasn't till 1966. But to me, he's always been an extremist." To Jerry Nelson, as to most black New Haveners, "extremist" means anyone willing to act on what he believes—all the time.

Black Panthers in New Haven? Too absurd to consider, even in 1968. The Panther Party was still a mysterious aberration of California-style nut politics. Black New Haven read about such things while white New Haven earnestly bulldozed. Bulldozers were the great weapon in the war on urban blight. Bulldozers ate up the ugliness and plowed under the obvious. City fathers ran their bulldozers over New Haven's inner-city neighborhoods for twelve years. By the time black folks woke up, downtown New Haven was gone. Removed. To be renewed. Dust soup.