|

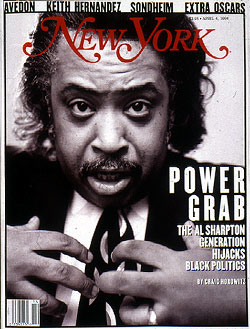

From the April 4, 1994 issue of New York Magazine.

On a damp, misty evening a few weeks ago, a small crowd had begun to gather at the corner of Decatur Street and Marcus Garvey Boulevard in Bedford-Stuyvesant. Cast in thick shadows by faulty streetlights, the group stood in front of the Bethany Baptist Church, collars turned against the chill, looking only at one another to avoid the eyes of the drunks and junkies who periodically stumbled by. It was the twenty-ninth anniversary of the assassination of Malcolm X, and most of the men and women waiting for the wooden church doors to open looked old enough to remember. Some wore African-style hats called co'ufees. Some wore buttons proclaiming I SUPPORT THE NATION or RESPECT THE BLACK WOMAN. One man carried a hand-lettered sign that read DUMP MOYNIHAN on one side and DUMP OWENS— Major Owens, the black Brooklyn congressman—on the other. A man from Queens in a gray double-breasted suit wore a scarf with the words U.S. SENATOR 1994 printed under a strikingly winsome picture of the Reverend Al Sharpton.

A rally was scheduled to start at 7:30, and as the time approached, the waiting crowd had grown into the hundreds. There were no wool caps, no hooded sweatshirts, no unlaced high-tops, no Timberland boots, no jackets with giant logos. This was not a crowd of people from the projects, the hard-core urban poor. And the majority carried no Afrocentric or political accessories. They were dressed as if they had just come from work, civil servants and lawyers, teachers and office temps, cabbies and beauticians, book-keepers and hospital workers—not the kind of crowd white people imagine at a rally for the Reverend Al Sharpton. But they had all come out on this dismal Monday evening to hear Sharpton announce that he would challenge Senator Daniel Patrick Moynihan in September's Democratic primary. They had also come out to vent their rage at conditions in their neighborhoods, to show their unhappiness with black elected officials, and to proclaim their support for a new wave of insurgents now looking to purge and replace the established black leadership. And by the time the rally got under way, there were more than 1,000 people packed inside Bethany.

Sharpton had gathered half a dozen of black New York's most contentious figures: activist and WWRL-radio personality Bob Law; lawyers and chronic race-baiters C. Vernon Mason and Alton Maddox; Adam Clayton Powell IV, movie-star-handsome Harlem city councilman and legatee of the most famous family name in the city's black political history; Sergeant Eric Adams, the radical head of the Guardians, the black patrolmen's association; and 28-year-old Conrad Muhammad, the leader of the Nation of Islam in New York.

Bob Law quickly set the tone for the raucous three-and-a-half-hour event. "This is the beginning of a movement. There must be a significant change in the leadership in our own community." Without mentioning Owens, Charles Rangel, or any other member of the Old Guard, he repeatedly called black incumbents "punks" and "cowards," men more concerned with advancing their own careers than with helping their communities. In a reference to the Louis Farrakhan—Khallid Muhammad controversy, Law charged, in his trained radio voice, that some black leaders didn't take care of their own people because they were "too busy driving Miss Daisy and then checking with her to find out who they can support and who they must repudiate." The crowd loved it.

"Teach!" screamed one woman in the back.

"Tell it, brother!" yelled a man from the balcony.

But this was Reverend Al's night, and when he stepped to the podium, which was draped in kente cloth, the crowd exploded. Squeezing the moment, Sharpton quietly listened to the cheering. Dressed in the clothes of a serious political candidate—dark suit, gray shirt with white collar, red tie, black wing tips, and no medallion—he seemed content just to experience the scene. With the shine, the red highlights, and the processed curls of his neo—James Brown coif, he looked as if he had just stepped out of a salon. Finally Sharpton was ready to speak.

"No justice!" Sharpton bellowed in his throaty baritone.

"No peace," they responded with a roar.

"What do we want?" he implored them.

"Sharpton."

"When do we want him?"

"Now."

Sharpton, who is five feet ten and has trimmed down to 270 pounds, was just getting warmed up. He was running on adrenaline now, and he was ready to demagogue the senior senator from New York. "Moynihan says the problem in the black community is single-parent families. Well, I was raised by my mother. What kind of misogynist are you that you blame helpless women? You beat up on them rather than do your job," he screamed as if Moynihan were there in front of him.