|

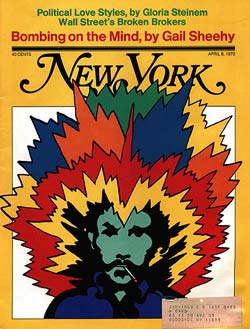

From the April 6, 1970 issue of New York Magazine.

Can that be Marc?

So thin. The young man stands on the steps of College Walk in a hooded Army surplus jacket, dwarfed by the mute stone geometry of one of our Great Universities. His pants hang. From 20 yards he looks like a stick figure in an architect's rendering . . . the kind they draw with a long shadow . . . a single movable stick figure in a grand concrete design. It is three days after Friday the 13th of March. Three buildings have been bombed in midtown Manhattan. Marc's friends are dropping out of sight. Ted Gold and his companions, who played with dynamite, are dead on West 11th Street. Jane Alpert, Dave Hughey and Sam Melville, for whom Marc helped to raise bail, face trial on charges of bombing two Manhattan buildings and a National Guard truck last summer. Marc knows these people. Inspector Finnegan and his subversive-chasing Red Squad know Marc.

Can that really be Marc? The silhouette is stark as an ailanthus tree, reedy and budless, waiting at the end of an oppressive urban winter for the cold spring to break. But Marc is a man, 29, Jewish, married, mild-voiced. He is dedicated to the liberation of practically everybody and normally suffers only from the standard afflictions of any white middle-class regular in the Movement: a lump of rhetoric in the throat and chronic love-hate disease.

Marc is not considered lunatic fringe. Neither was Ted Gold. Behind Marc's Fine Arts face is a brain in good working order. It has been through many changes since childhood in St. Louis. Marc is a weathervane. The way he goes, so go the prevailing ideological winds of radicalism. His last change was to commune-ism; he is developing an urban commune where young parents, living in the shadow of the university, can leave their children free, exchange clothes in a free store and generally experiment with the extended-family idea. Several months ago Marc talked of these things and of his 4-year-old child, Meredith. Was his son in school? I asked. Actually, he said, Meredith is a girl. We both laughed, because Marc's household is very heavy on Women's Liberation. Nevertheless, any Jewish mother would still love to have Marc's face in a frame on the bedside bureau. Mustache and all.

Now the young man scuffles hurriedly down the steps. Marc? The eyebrows arch up and touch, forming a pitched roof over his eyes. The mustache has dropped several notches. It hides his mouth with a dark V that matches the V of the brows, like two peace signs. Upside down.

"Hey, it's me," he says.

"Didn't recognize you."

"I know. I've lost a lot of weight. I lost 15 pounds in the last two months."

"Paranoia?"

"No. Fear."

Marc is preparing himself to die.

"When I get nervous I can't eat," Marc says. We are sliding trays around the cafeteria belt of Columbia's Lion's Den. Marc never went to school here but lives nearby. Since Abbie Hoffman gave the weather report on the campus last Fridayó"New York: BOOM BOOM BOOM"ófollowed by the weekend's window-smashing spree, Columbia is attracting visits from older, neighboring rads. They stop by with a sort of Parents' Day interest.

Marc puts down a cheeseburger. Nothing else. The police have questiond him in connection with the bombings. "My friend of two years turned out to be a police plant. My line is tapped, but that goes without saying." (Every self-respecting radical thinks his line is being tapped.)

A word hangs in the air, straining like those black helium balloons we all let loose over a sodden Sheep Meadow last Octoberóremember? The Vietnam Moratorium? Taps? A few tears, a new hope. And then we all went home and had tea. Today the word is bombing.

"I talked to a lot of people over the weekend," Marc says. "It surprised me."

"What did?"

"How many people relate to bombings."

Marc looks with condescension around the dining room, den of the Great University rads. The air hangs blue over their bridge games, tinged with the sweetness of grass.

"The most visible Left leaders are the most harmless," Marc says. "Look aroundó80 per cent here are new faces."

He clamps down on a Camel. His hidden eyes indicate that now we are going to talk about the under-underground movement, about the graduate revolutionaries of April '68 and the dispersed Weathermen and Mad Dogs and the Brooklyn Commune. Some are in jail. Others have made contact with better-hidden cells around the country (the figure given by one TV commentator, "based on academic sources," is 1,000 such cells). Three tenets of the under-underground are: Keep moving. Don't give your name. Form an affinity group. Four or five people who know and trust one another and are ready for heavy action, sharing a preference for the same tactic, make up an affinity group. In the past week the Weathermen have broken down still further; the members have spread out to work as individuals or with one other person. Then there are the roving anarchy advisers who travel the campus circuit. They appear to have staked out New York for their spring/summer offensive.