|

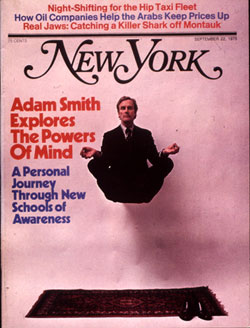

From the September 22, 1975 issue of New York Magazine.

It has been a year since I drove a cab, but the old garage still looks the same. The generator is still clanging in the corner. The crashed cars are still in the shop. The weirdos are still sweeping the cigarette butts of the cement floor. The friendly old “YOU ARE RESPONSIBLE for all front-end accidents” is as comforting as ever. Danny the dispatcher still hasn’t lost any weight. And all the working stiffs are still standing around, grimy and gummy, sweating and regretting, waiting for a cab at shape-up.

Shape-up time at Dover Taxi Garage #2 still happens every afternoon, rain or shine, winter or summer, from two to six. That’s when the night-line drivers stumble into the red-brick garage on Hudson Street in Greenwich Village and wait for the day liners, old-timers with backsides contoured to the crease in the seat of a Checker cab, to bring in the taxis. The day guys are supposed to have the cabs in by four, but if the streets are hopping they cheat a little bit, maybe by two hours. That gives the night liners plenty of time to stand around in the puddles on the floor, inhale the carbon monoxide, and listen to the cab stories.

Cab stories are tales of survived disasters. They are the major source of conversation during shape-up. The flat-tire-with-no-spare-on-Eighth-Avenue-and-135th-Street is a good cab story. The no-brakes-on-the-park-transverse-at-50-miles-an-hour is a good cab story. The stopped-for-a-red-light-with-teen-agers-crawling-on-the-windshield is not too bad. They’re all good cab stories if you live to tell about them. But a year later the cab stories at Dover sound just a little bit more foreboding, not quite so funny. Sometimes they don’t even have happy endings. A year later the mood at shape-up is just a little bit more desperate. They gray faces and burnt-out eyes look just a little bit more worried. And the most popular cab story at Dover these days is the what-the-hell-am-I-doing-here? story.

Dover has been called the “hippie garage” ever since the New York freaks who couldn’t get it together to split for the Coast decided that barreling through the boogie-woogie on the East River Drive was the closest thing to rid-ing the range. The word got around that the people at Dover weren’t as mean or stodgy as at Ann Service, so Dover became “the place” to drive. Now, most of the hippies have either ridden into the sunset or gotten hepatitis, but Dover still attracts a specialized personnel. Hanging around at shape-up today are a college professor, a couple of Ph.D. candidates, a former priest, a calligrapher, a guy who drives to pay his family’s land taxes in Vermont, a Rumanian discotheque D.J., plenty of M.A.’s, a slew of social workers, trombone players, a guy who makes 300-pound sculptures out of solid rock, the inventor of the electric harp, professional photographers, and the usual gang of starving artists, actors, and writers. It’s Hooverville, honey, and there isn’t much money around for elephant-sized sculptures, so anyone outside the military-industrial complex is likely to turn up on Dover’s night line. Especially those who believed their mother when she said to get a good education so you won’t have to shlep around in a taxicab all your life like your Uncle Moe. A college education is not required to drive for Dover—all you have to do is pass a test on which the hardest question is “Where is Yankee Stadium?”—but almost everyone on the night line has at least a B.A.

Shape-up lasts forever. The day liners trickle in, hand over their crumpled dollars, and talk about the great U-turns they made on 57th Street. There are about 50 people waiting to go out. Everyone is hoping for good car karma. It can be a real drag to wait three hours (cabs are first come, first served) and get stuck with #99 or some other dog in the Dover fleet. Over by the generator a guy with long hair who used to be the lead singer in a band called Leon and the Buicks is hollering about the state the city’s in. “The National Guard,” he says, “that’s what’s gonna happen. The National Guard is gonna be in the streets, then the screws will come down.” No one even looks up. The guy who says his family own half of Vermont is diagnosing the world situation. “Food and oil,” he says, “they’re the two trump cards in global economics today … we have the food, they have the oil, but Iran’s money is useless without food; you can’t eat money.” He is running his finger down the columns of the Wall Street Journal, explaining to a couple of chess-playing Method actors what to buy and what to sell. A lot of Dover drivers read the Wall Street Journal. The rest read the Times. Only the mechanics, who make considerably more money, read the Daily News. Leaning up against the pay telephone, a guy wearing a baseball hat and an American-flag pin is talking about the Pelagian Heresies and complaining about St. Thomas Aquinas’s bad press. His cronies are laughing as if they know what the Pelagian Heresies are. A skinny guy with glasses who has driven the past fourteen nights in a row is interviewing a chubby day liner for Think Slim, a dieters’ magazine he tried to publish in his spare time. The Rumanian discotheque D.J. is telling people how he plans to import movies of soccer games and sell them for a thousand dollars apiece. He has already counted a half-millions in profits and gotten himself set up in a Swiss villa by the time Danny calls his number and he piles into #99 to hit the streets for twelve hours.