|

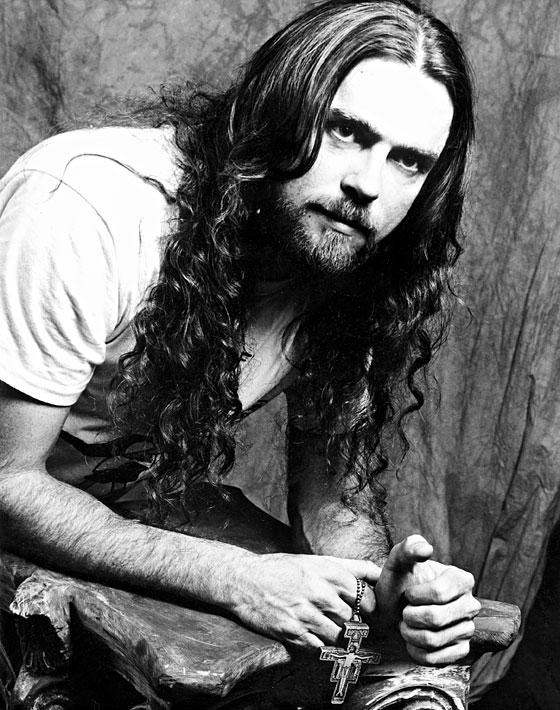

Activist, Baptist minister, and Housing Works co-founder Charles King.

(Photo: Bill Bytsura) |

The gay ghetto was a tinderbox by March 1987. Ten thousand New Yorkers had already become sick with AIDS; half were dead. Along Christopher Street you could see the dazed look of the doomed, skeletons and their caregivers alike. There was not even a false-hope pill for doctors to prescribe.

Then the posters appeared. A small collective of artists had been working on a striking image they hoped would galvanize the community to act. Overnight, images bearing the radical truism SILENCE = DEATH appeared on walls and scaffolding all over lower Manhattan. The fuse was set—and then the writer and activist Larry Kramer struck a match. He’d been invited to be a last-minute substitute for a lecture series at the Lesbian and Gay Community Center.

“If my speech tonight doesn’t scare the shit out of you, we’re in trouble,” he began. “I sometimes think we have a death wish. I think we must want to die. I have never been able to understand why we have sat back and let ourselves literally be knocked off man by man without fighting back. I have heard of denial, but this is more than denial—it is a death wish.” He concluded, “It’s your fault, boys and girls. It’s our fault.”

Just like that, a new, grassroots direct- action movement congealed. Within weeks it would adopt the name ACT UP (the AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power) and a deceptively simple demand: Drugs into bodies.

That was 25 years ago this month, and so much has happened since then, all of it stemming from that one electric moment. ACT UP revolutionized everything from the way drugs are researched to the way doctors interact with patients. Ultimately it played a key role in catalyzing the development of the drugs that since 1996 have helped keep patients alive for a near-normal life span. act up also redrew the blueprint for activism in a media-saturated world, providing inspiration for actions like Occupy Wall Street.

The leaders of ACT UP were shrewd and relentless—and they were also, inevitably, romantic figures. Photographer Bill Bytsura set out to memorialize those individuals, along with the movement’s rank and file, mid-battle. Over a six-year period, he shot 225 ACT UP members from New York, but also from Paris, Berlin, Amsterdam, Mexico City, and elsewhere. We recently rediscovered these pictures in the archives at NYU’s Fales Library. A small selection is presented here, along with present-day pictures of those, among this grouping, who survived—to live their lives, and to recall their extraordinary days in the trenches.

Charles King

King can’t remember where he was first arrested, but his last arrest was just last week, inside the Capitol Hill office of Representative Hal Rogers of Kentucky, co-author of the current federal ban on clean-needle exchange in the war against AIDS transmission. For King, who is a lawyer and Baptist minister, ACT UP changed his life unexpectedly when he found romance in a committee meeting: For fifteen years, he and

Keith Cylar, with whom he co-founded and ran Housing Works, were a storied couple. Cylar died in 2004. “I’ve never felt like I was in the inner circle” of ACT UP, King says. “I always thought I was one of the nerdy people off to the side, because I was religious. Keith didn’t think so.”