|

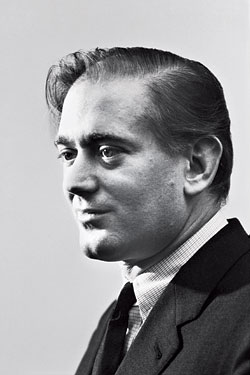

Felker at a New York party in 1967.

(Photo: David Gahr) |

I took a second look—I was right the first time. The man’s shirt had a button-down collar … and … French cuffs with engraved gold cuff links … a boy’s lolly boarding-school collar … and … a set of cuffs from a partners meeting at Debevoise & Plimpton … This shirt had to be custom-made … had to be. Likewise, the man’s jacket … Catch the high armholes and the narrow cut of the sleeves. They clear the French cuffs by a precise eighth of an inch. They’re just short enough—just so!—to reveal the gold cuff links and not a sixteenth of an inch shorter. Check out the shoes!—brown leather cap-toed English oxfords custom-fitted so closely to his high-arched feet, they look absolutely petite, his feet do, as if he were some unaccountably great strapping Chinese maiden whose feet had been bound in infancy to make sure they would be forever tiny at teatime … I could not imagine how a man his size, six feet tall and 200 pounds at the very least, with a big neck, a burly build, a square-jawed face, could possibly rise up from his chair here in a little bullpen slapped together out of four-foot-high partitions in the sludge-caked exposed-pipe-joint offices of a newspaper not long for this world, the New York Herald Tribune, and support himself, no hands, teetering atop that implausibly little pair of high-arched bench-made British cap-toed cinderella shoes.

Yet rise and stand he did. He introduced himself. His name was Clay Felker. He had a booming voice, but it wasn’t so much the boom that struck me. It was his honk. The New York Honk, as it was called, was the most fashionable accent an American male could have at that time, namely, the spring of 1963. One achieved it by forcing all words out through the nostrils rather than the mouth. It was at once virile … and utterly affected. Nelson Rockefeller had a New York Honk. Huntington Hartford had one. The editor of Newsweek, Osborn Elliot, had one. The financier Robert Dowling, publishers Roger Straus and Tom Guinzburg had the Honk, and so did Robert Morgenthau, who still does, as far as that goes.

Unfortunately, Clay Felker didn’t even rate being in the same paragraph with toffs like them. Custom-made toffery he was clad in, but he was also pushing 40 and jobless, on the beach, as the phrase went, panting, gasping for air, a beached whale, after coming out the loser in a battle for the editorship of Esquire magazine … not to mention the corner suite with north and east views of 1963’s street of dreams, Madison Avenue in the Fifties, that came with it.

Yet in less than six months from that same day, in that same jerry-built eight-by-ten-foot bullpen at a doomed newspaper, he created the hottest magazine in America in the second half of the twentieth century: New York.

In our story, the shirt (Turnbull & Asser of Jermyn Street, London), the suit (Huntsman of Savile Row, London), the shoes (John Lobb, also of Jermyn Street, London), as well as the accent, are not thrust into the reader’s face idly. All provide microscopic glimpses into our story’s very heart. And the duplex apartment Clay Felker lived in at 322 East 57th Street—well, from up here the view becomes what has to be termed macroscopic. The living room was a 25-by-25-foot grand salon with a two-story, 25-foot-high ceiling and two huge House of Parliament–scale windows, overlooking 57th Street, each 22 feet high and eight feet wide, divided into colossal panes of glass by muntins as thick as your wrist. There was a vast fireplace of the sort writers searching for adjectives always call baronial. Fourteen status seekers could sit at the same time on the needlepoint-upholstered fender that went around it, supported by gleaming brass columns. When you arrived chez Felker and walked out of the elevator, you found yourself on a balcony big as a lobby overlooking the meticulously conspicuous consumption below. Guests descended to the salon down a staircase that made the Paris Opera’s look like my old front stoop. Standing on the gigantic Aubusson rug at the foot of the stairs to welcome you, on a good night, would be Felker’s wife, a 20-year-old movie actress named Pamela Tiffin, who had starred in the screen version of Summer and Smoke. She had a fair white face smooth as a Ming figurine’s. She was gorgeous. She had something else, too, a career that was taking off so fast she had not one but two personal managers, Irwin Winkler and Robert Chartoff. She could afford them and two more like them, but there were no two more like them. Fifteen years later Chartoff and Winkler would win an Academy Award for a movie they produced called Rocky. For a man on the beach, Pamela Tiffin was a lovely helpmate to have. Clay Felker was broke.