|

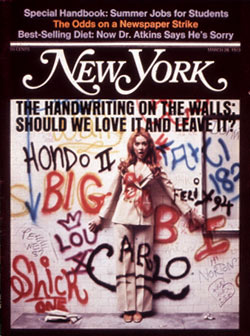

From the March 26, 1973 issue of New York Magazine.

Hard Times: New York's Neediest Cases

At this season, every two or three years, it has become customary to appeal to New Yorkers in behalf of a group of citizens in our midst whose need for understanding and support becomes heart-rendingly acute.

This group consists entirely of our three surviving daily newspaper publishers and the thirteen labor unions they must deal with in order to stay in business.

The periodic failure, often in odd-numbered years, of newspaper publishers and their unions to agree on terms for new contracts is one of the few reliable ways New Yorkers can tell that spring has arrived.

This year, we appeal to New Yorkers to have a special care for these fellow citizens. Contracts between the newspaper publishers and most of the unions expire at midnight, March 30, and the odds on their ability to reach new agreements this time around are unusually difficult to calculate. Ultimately, all issues in their disputes come down to a matter of money, but this time some of these issues are masquerading as matters of principle. Should this confusion persist, participants on both sides of the table would be venturing on new, and therefore unpredictable, ground.

New Yorkers may be sure that their sympathy, whether applied or withheld, will not make the slightest difference. Previous strikes, to say nothing of the death of four dailies in the past ten years, have proven that New Yorkers can live without newspapers altogether.

In any case, the issues standing in the way of a new agreement will be resolved in total indifference to the needs and temper of the general public. Settlements are invariably reached only when each side becomes convinced, all over again, of the other's willingness to commit economic mayhem—through a strike, a lockout, or other tactic—in order to make its position clear and credible.

But your gift of understanding to the needy cases described below will speak well of you as a person.

All of the stories on these pages are true. In some cases, the identity of a person uttering a useful observation has been withheld at the person's insistence. This is because people involved in the publication of newspapers often believe that what they really think is nobody else's business.

In all cases, the plight of these needy has been attested by audited statements, plus verifiable rumor or common gossip.

[Case 101]

A Scion's Struggle

Arthur S. is now 47. Grandson of the founder-publisher of our modern New York Times and son of that great man's worthy successor and son-in-law, Arthur S. was a late child, preceded by three sisters and a good deal of speculation, if not anxiety, about a male child's ever coming.

In 1963, at the tender age of 37, Arthur S. acceded unexpectedly to the position of publisher of The Times. He was called on to demonstrate his fitness to command the best newspaper in the country before a notoriously skeptical audience consisting mainly of journalists and other publishers, some of whom confidently expected —perhaps even hoped—that he would fall on his face.

Psychologists agree that this is an unpleasant spot to be in.

For much of the ensuing decade, it had been Arthur S.'s cruel lot in labor negotiations to resist new wage demands while The Times's profits were bordering on the obscene. In the past three years, however, The Times's earnings have fallen precipitously—from $31 million in 1969 to $13 million (pre-tax) last year.

The decline coincides with a three-year labor contract Arthur S. had agreed to in March, 1970, an agreement that more closely resembled a suicide pact. Minor variations aside, the contract called for money increases in various forms (in retirement, health, or other benefits as well as wages) amounting to 15 per cent the first year, 11 per cent the second year, and another 11 per cent the third year—a 42.69 per cent boost, compounded, over the life of the contract. In return, The Times got absolutely nothing from the one union it most urgently needed something from—Local 6 of the International Typographical Union. The Times and Big Six could not agree on ways to permit the introduction of new equipment that would lower The Times's production costs.

As the presumed boss of The Times, Arthur S. has taken much abuse for going along with the "15/11/11" formula and getting nothing in return (except, of course, three years of peace). He has been vilified by his peers in town and across the country. He has been relentlessly second-guessed by colleagues within the Times building on West 43rd Street. He has even been spoken of contemptuously by some of the very union leaders who engineered his consent. "He is soft," they said privately.