|

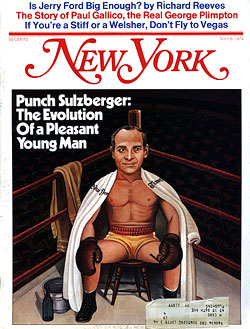

From the May 6, 1974 issue of New York Magazine.

Sons of distinguished fathers have to count themselves lucky if the world, out of spite or envy, does nothing worse than condescend to them. Arthur Ochs (Punch) Sulzberger may one day conclude that he was even luckier than that, for the worst that the world has been able to do to him since 1963, when he inherited the title and powers of publisher of The New York Times, is underrate him.

The newspaper he took over eleven years ago was secure in its reputation as the best in the business. It seemed so perfectly designed for making money that most observers thought that any amiable cipher could be installed at the top without harm. Although it continued to make fat profits through the sixties, The Times in fact was, by the standards of modern business practice, a mess—ignorant of any profound knowledge of budgeting, planning, or coherent growth strategy, and lacking, at the highest levels, young blood.

Worse, for the immediate harm it was doing, The Times had acquired a reputation, fully deserved, for being gutless and obtuse in its labor negotiations. Its lame posture at the bargaining table was almost a matter of principle. "Under my father," Punch Sulzberger remembers, "it was the policy that The New York Times would never take a strike on an economic issue." Slow to shed the burden of that heritage, Sulzberger in 1970 acquiesced in a humiliating agreement with Local 6 of the New York Typographical Union, led by the redoubtable Bertram Powers, in which The Times agreed to boost printers' wages 43 per cent over the next three years and in return got nothing on the vitally important issue of automation in the composing room.

But last week, as he faced up to yet another negotiation with Bert Powers, Punch Sulzberger could rightly claim to have remade not only The Times but The New York Times Company, which owns the paper and of which he is chairman and president. By the standards of modern business practice, The Times Company is now up to snuff—with tightly disciplined budgets, sophisticated planning techniques, a demonstrably successful diversification strategy, and, at the highest levels, a team of young managers who had implemented these practices.

Better still, for the immediate good it could do, The Times Company had spent the past four years systematically psyching itself up to take a much harder line in dealing with Bert Powers. The 1970 negotiations with the Typographical Union had traumatized Sulzberger. "It was a reasonably humiliating experience," he recently recalled. A Times executive with long experience in finding exact equivalents in forceful English for Sulzberger's habitual understatements offered the following translation: "After Bert Powers had finished marching around in our composing room, we resolved that that son of a bitch was never going to do that to us again."

In direct consequence, Punch Sulzberger began clearing out dead-wood executives and imposing budget discipline in earnest, and he intensified his search for other properties that would reduce the company's dependence on The Times's profits. Last week it was clear that The Times Company could risk taking a hard line with Bert Powers because it could afford to. In 1970, the year of its humiliation, The Times accounted for some 80 per cent of the company's total earnings, which were not especially robust. In 1973, as a result of some highly profitable acquisitions, the newspaper accounted for just 60 per cent of total earnings, and the earnings themselves had soared close to an all-time record.

The pattern has continued in 1974. At his annual meeting last Tuesday, Punch Sulzberger reported the largest first-quarter profit in Times history. The company's earnings base had broadened so much in four years that, with the pre-Easter advertising revenue already tucked away, Bert Powers could shut the paper down tomorrow and keep it shut for the rest of 1974, and The New York Times Company as a whole might do no worse than break even on the year.

It amounts to an extraordinary change in The Times Company's fortunes and temper, but the transformation has gone all but unnoticed, especially on Wall Street. In 1969, with things soon to get much worse for the company, Times Company stock traded as high as 53. Last week, with things obviously better and the possibility of a strike not really relevant ("Don't sell on a strike" is an old trader's maxim), Times stock traded at 10˝. "If all this had happened with a new guy in charge, it would be a major business story," an investment manager who follows Times stock closely said recently. "But it's the same guy, just Punch, so no one is noticing."