|

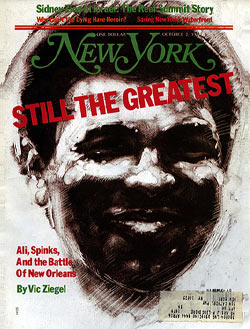

From the October 2, 1978 issue of New York Magazine.

Do you know if I beat him the first time I wouldn't of got no credit for it. He only had seven fights . . . the kid was nothing. . . . So I'm glad he won. It's a perfect scene. You couldn't write a better movie than this. This is it. Just what I need. Competition. Fighting odds. Can the old champ regain his title for a third time? Think of it. A third time. Do or die. And you know what makes me laugh? He's the same guy. Only difference is he got eight fights now.

柚uhammad Ali on Leon Spinks before their championship fight

The copy of Money magazine offered to Leon Spinks during his flight to New Orleans was full of splendid suggestions for a new career. Soccer coach, that was something the heavyweight champion might want to think about. Nowhere is it written that soccer coaches have to run through strange cities at five in the morning. Or spend great hunks of each day inside expensive hotel rooms that offer baskets of apples and Gouda instead of X-rated film selections. And there aren't small armies of people telling the cover-boy soccer coach to kick this, do that, no this, no, no, no . . . armies that depend on the heavyweight champion to provide their per diem expenses.

The magazine went unread, of course. Leon Spinks was in Louisiana to defend his title against Muhammad Ali, a 36-year-old body with the staying power of Tutankhamen. Ali was the favorite. Ali was the attraction葉he once, twice, and future champion. Leon Spinks? Come on. Just another name on an expired driver's license.

"Did you hear what Spinks did when he came off the plane?" The lawyer is talking to a sportswriter after the fight. The party is at the Windsor Suite of the New Orleans Hilton. Sportswriters are badly outnumbered by designer suits. Worse yet, the lawyers had heard all the best available fiction.

"Spinks gets off the plane and he does an interview. Everything's cool. No problems. And then they hustle him into the sheriff's private car to drive him to the hotel. The first thing he does葉his is in the sheriff's car, right?葉he first thing he does is take out a joint and light up."

Leon Spinks was taking a terrible beating in this Windsor Suite soiree. Bob Arum, the promoter who brought the fighters together and sold them to television for $5 million, controlled the rights to Spinks's first six title defenses. Poof, all gone. But this was no time to mourn. Another of Arum's champions, Danny "Little Red" Lopez, a rock-fisted 126-pounder, had survived a first-round knockdown to render his opponent unconscious one round later. And Arum had an unexpected bonanza in Mike Rossman, the light-heavyweight son of an Italian father and Jewish mother who fights with the Star of David on his trunks and shoes. (If you've got it容ven when it's your mother's maiden name遥ou flaunt it.) Rossman, 22 years old, became champion after stopping Victor Galindez, the longtime titleholder.

Rossman and Lopez葉he promoter was delighted with both of them. Those were the names he repeated. Leon Spinks? "What a waste of talent," Arum said. "He was drunk every night for the two weeks before the fight."

Muhammad Ali, on the other hand, was taking care of business. He so desperately wanted to become the first boxer to win the heavyweight title three times that he decided on a strategy he had previously abandoned: He trained. When he stripped to the waist for the first time in New Orleans, there was no sign of the jelly doughnut above his belt. "I want you to know I'm real serious for this fight," Ali said. "Put your money on me. I cannot get no better."

He rented a home in West Lakeside, a New Orleans suburb, and rarely visited the hotel's fight headquarters. "We're getting police protection like I never seen," said Gene Kilroy, who calls himself Ali's business manager. "About every five minutes a cop car drives down our street real slow. They want what everybody else wants . . . see if they can spot Ali, get an autograph."

The business manager had an easier time of it for this fight. Ali's entourage was issued dated vouchers, $25 a day, and there were no newcomers with expensive habits. "Before we went to Los Angeles for the second Norton fight," Kilroy remembers, "Ali met a guy in New York and flew him out to the coast. He gives the guy a room in the hotel. Then the guy decides to throw a party to tell everybody Ali's his friend. Only the room ain't big enough so he gets the hotel to open up the adjoining room for the party. And he sends flowers to Ali. Later I'm going over the bills for the fight, and there's one bill for the flowers and another for the party, $3,600.