|

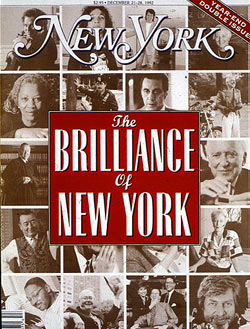

From the December 21-28, 1992 issue of New York Magazine.

Pat Riley is in search of character and excellence. Nothing less. He is convinced that they go hand in hand. Most people, he says, think they work hard, but in truth, they really don't. They are not willing, once they achieve a level of success, to make that constant extra effort to extend their abilities to the highest level. This is true about almost every aspect of life, he thinks, and it is particularly true about professional basketball. He is not impressed by talent without character. He read David McCullough's splendid biography of Truman and was impressed not just by the quality of the book but by McCullough's work habits. Riley is always on the lookout for the defining moment when character manifests itself; with McCullough, that came when the biographer walked the same steps that Truman had walked on the day he received the news of Roosevelt's death. That, to his mind, was excellence.

Excellence, it should be noted, exists in things both great and small. Thus, there was the cable he sent his former broadcast partner Bob Costas for the exceptional job Costas was doing as the anchorman of the Barcelona Olympics, a job worthy of Riley's expectations. Still, there was a flaw in Costas's performance that bothered Riley. So his cable arrived several days into the games, congratulating Costas for his work. Then came the zinger: "But the ties, Bob, the ties!"

Riley has always driven himself to maximize his own talents. The world of basketball was changing while he was still in college in the mid-sixties. It was clear to him early in his pro career that he would never be a star and that just staying in the game would be a challenge. After three years with the then—San Diego Rockets (and coming perilously close to the tail end of his own professional career), he had a chance to stay in the league by signing with the Lakers. His marching orders were very clear. "Do you want a job on this team?" Fred Schaus, the general manager, asked. "Your job is to keep Jerry West and Jimmy McMillian in shape—to push them very hard every day in practice. Don't back off them. Make them work hard." So he stayed in the league as practice fodder. He gladly took the job and the assignment that confirmed the most elemental lesson of life: that the great sin was to be outworked by someone else at anything. It kept him in the league for five more years, and it meant that he went against one of the great players of all time every day in practice, in itself an education.

When he became coach for the Lakers, his strengths were often lost amid the obvious talent of his players. The Lakers, after all, had Kareem, Worthy, and the remarkable Earvin Johnson, a player whose sense of achievement came only from the success of others. Certainly, coaching a team with Magic Johnson gave him an asset few others had. "Somehow, unbeknownst even to himself, he had already learned the most important thing in life: He had learned that to get out of the game what he wanted—which was to be a winner—he had to use his rare abilities to help his teammates get out of the game that which they wanted," Riley says admiringly of Johnson. Coaching the Lakers, therefore, always looked easier than it was: Just wear Armani suits, comb your hair back in a style straight out of Gatsby, give Magic the ball, coast through the season, hope to beat the Celtics or the Pistons in June, and then hand out the rings. Instead, the real challenge was keeping so much talent so finely tuned in a league where the young players are millionaires now before they hit their first shot: It was a constant challenge making sure that their rings were on their fingers and not in their heads.

The best thing about the extraordinary job Riley did with the Knicks last year—taking a seriously flawed group of overachievers, and guiding them to 51 wins—was that everyone who cared about basketball understood for the first time how good he was, and it cast his previous achievements with the Lakers in a different light; self-proclaimed connoisseurs of the sport began to reflect on the Laker years, on how easily that very same group of egocentric young millionaires might have unraveled even earlier. As it was, his tour there lasted nine years, and it ended only when it became clear that the demons that drove him for excellence were no longer matched by the demons that drove his players. It was time for him to go. He broadcast for one season and did it well and might, if he had wanted to, have done it even better; he worked hard in his new apprenticeship—Costas, his partner, was impressed not so much by Riley the broadcaster as by Riley the student of broadcasting, and by his hunger to learn. It was also true, however, that he never entirely committed himself to broadcasting, that he was careful never to say anything over the air that might be used against him if he ever decided to go back to coaching.