|

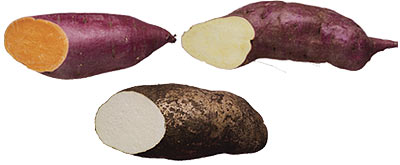

Clockwise from top left: Beauregard (mash it), Purple Japanese (roast it), Yam (don't call it a sweet potato).

(Photo: Davies + Starr) |

First, a note on sweet potato/yam confusion. Although the two vegetables are botanically distinct and very different in taste and texture, they’re similar in appearance and are widely confused by American tuber eaters. The terms, in fact, are often used synonymously, in error. The confusion, food historians believe, might date back to the arrival of slaves, who may have introduced the word because the American sweet potato looks similar to the African tuber.

So, to correct the side-dish record: A yam is a starchy tuberous root primarily of sub-Saharan African origin that’s also grown in the West Indies, Asia, and Central America. There are more than 600 yam species grown around the world, but true yams are rarely grown in the U.S. or sold here outside of specialty and ethnic markets. Yams are generally very starchy, fibrous even, and not especially sweet. Unless you grew up eating them, you probably won’t want them on your Thanksgiving table.

A sweet potato, on the other hand, is the sweet tuberous root of a tropical vine that’s related to the morning glory and is native to Central America and Peru. Columbus discovered the sweet potato in the New World on the island of St. Thomas. Today in the U.S., sweet potatoes are grown in Louisiana, South Carolina, and North Carolina and make up the vast majority of what consumers think of as sweet potatoes and yams. Some markets even sell sweet potatoes as yams, for the simple capitalist reason that consumers seem to like to buy them that way.

Sweet potatoes are of two dominant types, dark-skinned and light-skinned. The dark-skinned variety—the type commonly confused with yams—has a thick, dark orange skin with a bright-orange flesh that’s sweet and moist. The light-skinned sweet potato, with a thin, light-yellow skin and pale-yellow flesh, isn’t as sweet and has a drier texture, more like a regular baking potato.

Korean-born Nevia No was practically raised on sweet potatoes; they were eaten at breakfast, lunch, and dinner, and all day as a healthy snack. She now grows three varieties—Beauregard, purple Japanese, and white—at Yuno’s Farms in Bordentown, New Jersey, her 100-acre fruit-and-vegetable operation. For the requisite Thanksgiving side dish, boiled and mashed sweet potatoes topped with a marshmallow crust, No recommends using the Beauregard, as it has a soft texture that mashes smoothly. For a less traditional preparation, No likes to roast light-skinned sweet potatoes in their skin; as the water evaporates, the sugars are concentrated and they become sweeter, she says. Her sweet potato of choice for roasting is the purple-skinned Japanese sweet potato with ivory flesh. It cooks up fluffier and drier than other varieties, she says, and has a nutty flavor reminiscent of a chestnut. (Sweet potatoes should never be microwaved, No says. They become fibrous.)

Sweet potatoes, like baking potatoes, should be heavy for their size, firm, not yielding, and free of mold, blemishes, and sprouts. They should also have a taut, not wrinkly, skin. Sweet potatoes should be stored in a cool, dark place. If sweet potatoes become chilled, they can suffer from “hardcore,” and the center of the root will remain hard no matter how long it’s cooked.

Where to Buy

Yuno’s Farms at Union Square Greenmarket, Whole Foods (various locations), and Garden of Eden (various locations) offer excellent selections of sweet potatoes from 79 cents per pound.