|

(Photo: Brenda Ann Kenneally) |

David has a recurring dream. “Mi sueño nuyorquino,” he calls it. His New York dream. He’s flying high above Manhattan—his arms outstretched, a cool wind in his face. Far below on the streets, people point up at him, their eyes wide. It’s his favorite dream. “I have it often when I’m sleeping,” he says. “Being up so high, a loneliness that actually feels good. And the americanos noticing me.”

David doesn’t attract much notice in his waking life. He’s short and soft-spoken, with a face the color and shape of a homemade cookie. He dresses in bargain jeans and a sensible sweatshirt and keeps his head down. He decorates dishes with artful streaks of sauce and careful radish rosettes at an upscale West Village restaurant that’s perennially praised in Zagat’s for its beautifully presented food. When, after a few margaritas and some pato en mole verde, diners ask to tour the kitchen and compliment the staff, he greets them with a courteous nod and labored English: “How are you? Have a nice day.”

His housemates work at similarly bright and airy places such as Fairway and Citarella, bustling about the frisée bins and sautéing the portobellos and packing up comfort foods for harried professionals. As a household, they do pretty well even by New York standards, pulling in six figures a year. But this household is different from most in Manhattan. For one thing, there are 27 people in it—all Mexicans, most of them undocumented.

According to a recent City Planning Department study, two-thirds of all Mexicans in New York live in overcrowded conditions, the highest percentage of any immigrant group in the city. Twenty people in a Staten Island house built for six, eight in a Queens studio apartment, five in four narrow beds on Broadway just south of Columbia University. Clothes squeezed into liquor-store boxes, the toilet always occupied, the air rank with the smell of too many bodies in one place.

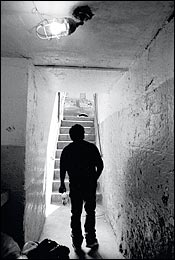

To get to his home, David walks past a phalanx of grand old Washington Heights high-rises full of classic sixes with Hudson River views and turns down a stairway that’s practically hidden from the street. He crosses a reeking courtyard strewn with waterlogged cardboard boxes, rotting chicken bones, and junked toilets and comes to a greasy window guarded by a Yosemite Sam doll holding a sign that reads BACK OFF, VARMINT. Next to the warning is a locked door, and past that, the dank, dark basement bowels of a pre–World War I apartment building. He passes the ancient and rumbling boiler and proceeds down a moldy hall not much wider than the corridor of a Pullman sleeper. To the right is the bathroom, whose ceiling opens to a maw of boards, with water and roaches seeping in. Farther on are several tiny rooms whose rickety doors are bolted with padlocks. One is David’s.

“Welcome to mi casa,” he says, opening the door to an eight-by-ten-foot space jammed with a children’s bunk bed, a refrigerator salvaged from the trash, and an outsize, cast-off TV. He shares the tiny room with a construction worker named José, who rehabs bathrooms and baby nurseries on the Upper West Side. For $100 each, they get 40 square feet apiece—half the 80 square feet required by law for each person in a household. It’s hard to turn around and impossible to walk anywhere but to the leaking bathroom down the claustrophobic hall, or to the small living room with the scavenged sofa and the saint-and-candle-clotted shrine to the Virgin of Guadalupe.

Twelve of the 27 people in the basement live in this 750-square-foot section. In addition to David and José, there’s Leo, Giovanny, and Paco, who work at Citarella. Mateo, Jacobo, and their roommate work at Fairway. Another guy works in a bar on 24th Street; his roommate does odd jobs in Washington Heights. Arianna boxes crayons at a factory in New Jersey. And Francisca trucks through the neighborhood with an old shopping cart, collecting soda cans for recycling. Individually, they’re poor. Collectively, they earn over $150,000 a year and pay $1,200 a month in rent.

Their decrepit basement apartment is illegal, of course. It was converted by a rotund Mexican affectionately known to the housemates as El Gato (the Cat). First he cleared out a half-dozen tiny toolrooms and wired them for electricity. Then he jerry-rigged a toilet and shower near the coin-operated washer-dryers used by residents of the 40-plus legal units upstairs. The building's landlord collects almost $3,000 in monthly rent from the two sides of the basement. Half he kicks back to the super, a Cuban. The super lets Gato live in the basement for free and funnels him some of the kickback in exchange for keeping up the apartments and recruiting a continuing supply of Mexicans. Gato has been here twelve years and has a rep for helping newcomer compatriots. He rounds up used clothing for them and organizes Sunday pickup basketball games so they won’t feel homesick.

But Gato’s efforts don’t help much. David and the others are “lonely boys,” men who come by themselves from Mexico to support the families they’ve left behind. Inside their crowded dwellings, they lead strangely isolated lives. “You feel like a ghost,” says David. “A ghost in a basement.”

David comes from a slum just south of Mexico City. His father used to work in construction, but he had an accident a few years ago that left him paralyzed. Now his mother sells fruit and vegetables on the street and makes the peso equivalent of $10 a day—which sounds impossible but is still twice the Mexican minimum daily wage. There are eight children in the family. Though all are now adults, the younger ones attend junior and business colleges and still have to be supported on that $10. David, 35, is the oldest and has always felt responsible for his sisters and brothers. At the same time, he harbors a certain irresponsibility, a yen for what he calls aventura.