|

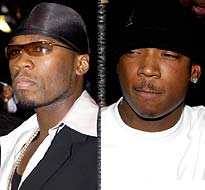

Gangsta Warfare: Rappers 50 Cent and Ja Rule

(Photo: Globe Photos) |

The subway ride from Manhattan to the 179th Street station in Jamaica, Queens, is so long that when you come up the stairs and into the light of the street, you feel as though you have jet lag. It’s the last stop on the F line, a neighborhood so outer-borough it might as well be in another state. Head south, cross Jamaica Avenue, and pass through a desolate area of abandoned buildings and trash-strewn lots dubbed “Bricktown” by the locals, and you’re in one of hip-hop’s fertile crescents. At the corner of 134th Avenue and Guy Brewer Boulevard, a small-time teenage hustler named Curtis Jackson—who would find much greater success as a rapper named 50 Cent—was busted selling crack and heroin to an undercover cop. A few blocks away is Woodhull in Hollis, a middle- class oasis among the crack chaos where a sweet-faced kid, the child of Jehovah’s Witnesses, named Jeffrey Atkins—who would rename himself Ja Rule—hung out on doorsteps with his buddies, eagerly knocking fists (giving a “pound”) with anyone who crossed his path. Looming over everything is Baisley Park, one of the city’s toughest housing projects, which was controlled in the late eighties by a drug lord named Kenneth “Supreme” McGriff. At his height, he had more than 100 employees—including, says a source, Curtis Jackson’s crack-addicted mother, Sabrina, who was murdered in 1984. McGriff’s “Supreme Team” sold crack, chanting the slogan “No dollars, no shorts”—street slang for no singles (hard to launder) and no discounts. McGriff, now 42 and in a federal prison on a gun conviction, was the image of ghetto success in the most violent epoch in New York’s history. Now the government is investigating whether he used his drug money to fund Irv “Gotti” Lorenzo’s Murder Inc., Ja Rule’s record company.

The Supreme era once again haunts hip-hop. Violence, both verbal and actual, has been escalating to a level not seen in a decade, as 50 Cent, Ja Rule, and McGriff play out roles rehearsed on the street corners of their youth.

With its welter of long-running plot lines, hip-hop has always had more than a passing resemblance to pro wrestling—drama is what it’s called in the hip-hop world. With one crucial difference: It’s real. In Ja Rule’s recently released disc Blood in My Eye, the violence is verbal—“I’ll probably go to jail fo’ sending 50 to hell”—but three years ago, it was physical. In March 2000, outside the Hit Factory studio on West 54th Street, 50 Cent was beaten and stabbed by Lorenzo, his brother Christopher, and a Murder Inc. rapper named Ramel “Black Child” Gill. Now hip-hop’s elder statesmen—from Russell Simmons to Louis Farrakhan—are worried that it’s heating up again—this time to lethal effect. The feud has drawn in other rappers, D.J.’s, and dueling hip-hop publications; The Source (anti–50 Cent) and XXL (pro) have been denouncing each other in editors’ letters and burning copies of each other’s magazines. It’s even leapt across continents: In July, a member of Ja Rule’s posse threatened to break the neck of a D.J. in Durban, South Africa, simply for playing 50 Cent’s song “21 Questions” after Ja Rule’s set there. The hottest mix tape on New York’s streets is “Street Wars,” which provides a blow-by-blow of the industry’s current beefs.

“Beef” is a time-honored hip-hop tradition—as well as a time-honored PR stunt. 50 Cent’s knocking-on-death’s-door image—after he was famously shot nine times, and lived to tell about it, he and his 6-year-old son, Marquise, sport matching bulletproof vests—is as much a part of his appeal as his laconic drawl, melodic choruses, and memorably odd (“berf-day”) pronunciations, which are said to be a result of a bullet to his mouth. It’s his violent rep that 50 Cent feels gives him unimpeachable authenticity, separating him from hip-hop’s faux gangstas, whom he derides as “wankstas.” “I think the industry would prefer a studio gangsta rather than someone who actually comes from that background, because it’s less of a risk,” 50 told me. “ ’Cuz you’re investing money in this person as an artist—and shots could go off.”

Indeed, when shots did go off—on May 24, 2000—his first label, Columbia, dropped him even though the streets were already buzzing about his song “How to Rob,” in which he fantasized about mugging hip-hop and R&B superstars. “After I got shot, they got afraid,” 50 Cent says. “Afraid of me in their offices.” But it was that story that convinced Eminem to bring 50 Cent to his label at Interscope Records. “His life story sold me,” Eminem told XXL in March. "To have a story behind the music is so important.” Eminem’s instincts were spot-on: 50 Cent’s Interscope debut, Get Rich or Die Tryin’, sold an astonishing 872,000 copies in its first week and will likely be 2003’s best-selling album.

For Ja Rule, on the other hand, being embroiled in this beef has brought dwindling rewards. At the turn of the millennium, Ja Rule’s empathetic duets with Murder Inc. labelmate Ashanti made the pair the Marvin Gaye and Tami Terrell of the hip-hop generation. But in early November, as 50 celebrated the launch of a new sneaker line named for his G-Unit Crew at downtown hotspot Capitale, the first-week sales of Ja Rule’s Blood in My Eye, which is rife with over-the-top threats against 50 Cent, were the worst in his history at Murder Inc. A source close to the label says that even before its release, Lyor Cohen, president of Def Jam, the parent company of Murder Inc., was so concerned about Ja Rule’s diminished street credibility that he tried—unsuccessfully—to enlist notoriously thuggish hip-hop exec Suge Knight to release Blood in My Eye on his Tha Row label.