|

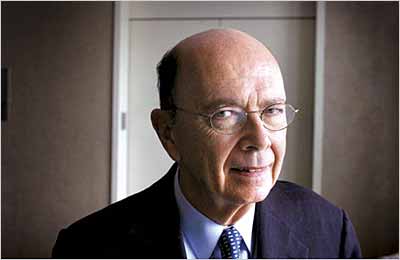

(Photo: John Chapple) |

For a private-equity investor who specializes in collecting underperforming assets in the industrial heartland, it was a nightmare come true. Wilbur Ross Jr., the Manhattan billionaire, had just gotten out of bed on January 2 when he received a frantic call: There had been an explosion in a mine he owns in Sago, West Virginia. Thirteen miners were trapped underground—some two miles from the mine shaft’s opening—a disaster that would soon command the attention of the international media.

“My initial reaction was to get on a plane and go to the mine,” Ross says via e-mail, “but our CEO, Ben Hatfield, felt that since I had no technical skills to help with the rescue process, I would just be in the way.” Instead, Ross worked the phones from his home office, hoping against hope that the miners were alive.

What followed was brutal press coverage that painted him as a heartless latter-day nineteenth- century coal baron. Such an outcome is really an occupational hazard for investors like Ross who, from the hushed confines of their offices in Manhattan, trade in companies that employ armies of industrial workers working in hardscrabble and sometimes dangerous conditions.

The blast shattered an extraordinary streak for Ross. The former husband of Betsy McCaughey Ross, Ross splits his time between Fifth Avenue and Palm Beach. He spent decades as an investment banker. In 2002, Ross started snapping up decaying steel mills, southern textile mills, and mines, earning him the nickname “Bottom Feeder” and vaulting him into billionaire ranks for the first time. His third marriage, to Hilary Geary in 2004, was toasted by Bobby Short at the Rainbow Room. This past November, he took over the International Coal Group, owner of the Sago mine.

And then: the explosion.

Ross became the target of recriminations from victims’ families, whose emotional swing, from initial terror to elation to rage and grief, riveted the nation. The press has pointed out that the mine had 202 federal safety violations last year (most of which predated Ross’s ownership), including sixteen that were seen as immediate hazards to miners’ safety. Ross has said he was assured by managers that the mine was safe.

“I don’t know what is harder—trying to get to sleep at night with Sago hanging over me or getting up in the morning to face another day of internal sorrow and external criticism,” he says, adding that he’s offered to personally match any contributions to the families from the public “dollar for dollar.” One of his fiercest competitors, Massey Energy Company, has pledged $250,000, and Ross adds that fellow city moguls have chipped in, including Donald Trump, who gave $25,000.

He’s still tormented by guilt, however. “For the rest of my life, the memory of those who died at Sago will haunt me,” he says. “That will never go away. I know that the families will wonder whether there wasn’t something more I could have done to make sure their loved ones would still be alive.”