|

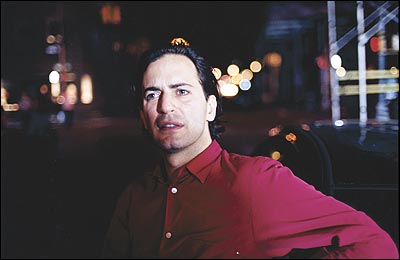

(Photo: Ryan McGinley) |

“I love a blouse that’s dumb,” says Marc Jacobs five weeks before his spring 2006 fashion show. Today he’s interested in proms (“all American ceremonies, really”), a funny black bow from a brown vintage dress, Rufus Wainwright, Scout Niblett, and gabardine. “I love to use the word dumb. It’s not knowing, and the word blouse is so out of fashion that I love it—a blouse that’s dumb. And gabardine. That’s what people need to be wearing right now.”

Why?

“I don’t know.”

He says it again, wrinkling his brow for emphasis.

“Gabardine.”

When Marc Jacobs is in New York, he starts his mornings early, with toast and jam at the Mercer Hotel (where he stays when he’s here; he lives most of the year in Paris), followed by sessions with a therapist uptown. By four o’clock, he’s wired on caffeine (endless Diet Cokes, emptied into endless plastic cups of ice) and nicotine. On this particular Friday, he’s made a trip to a costume shop, and he’s had a computer lesson on his new Mac from the “kids” in his design studio—first order of business: Google “Rufus Wainwright,” for no particular purpose—and now he’s in his office, sitting beneath a watercolor by Elizabeth Peyton of Sofia Coppola in a green sundress. He’s explaining the appeal of his clothes, which is not unlike the warble of Wainwright, whose album plays in the background: complicated and offbeat. So offbeat, Jacobs insists, that his clothes could never be quite as popular as clothes by Tom Ford or Ralph Lauren or Calvin Klein.

“It’s more psychological,” Jacobs says. “For people that don’t have any interest in the psychology of nuance, who need everything to be in their face, who don’t want to analyze . . . those aren’t the people I romanticize about dressing.”

It’s a version of fashion that dictates that when Gisele Bündchen is booked for a fashion show, a certain amount of consideration be given to unsexing the sexpot. “We always say, ‘Gisele’s so hot, how do we break her down?’ ” (Dumb, blouse, and gabardine, along with frumpy, dowdy, and fucked up, are Jacobs’s favorite words.)

“I don’t have any problem with what people refer to as sexy clothes,” Jacobs says. “I mean, everybody likes sex. The world would be a better place if people just engaged in sex and didn’t worry about it. But what I prefer is that even if someone feels hedonistic, they don’t look it. Curiosity about sex is much more interesting to me than domination. Like, Britney and Paris and Pamela might be someone’s definition of sexy, but they’re not mine. My clothes are not hot. Never. Never.

“When I first went to Vuitton, I spent so much time comparing myself to Tom Ford, and Gucci was, like, this sexy thing. You needed no explanation.”

Jacobs’s clothes do, sometimes, require explanation, as well as a healthy sense of irony. With the wrong attitude, the wrong body, and without the right wink, wearing Marc Jacobs clothes could leave a girl looking a bit like Mrs. Doubtfire.

“More people understand what Tom does. It’s so basic, and that’s not a put-down,” Jacobs says. “I think that’s so incredibly smart and focused, but it’s exactly what I shy away from. There’s a first-degree no-brainer definition of what’s sexy, but the reality of it is, what I find more interesting is someone who is more introverted or mysterious. When we have done sexy, I have thought of clichés like, Oh, she’s the bad Connecticut housewife, or She’s like Mrs. Robinson. I’ve got plenty of sexual female icons, but it’s not overt. It’s not an Über-woman, it’s not a power-hungry vicious man-eater. Youth to me is the most beautiful and sexy thing, really. I’m by no means a pedophile, but there’s a purity to youth. There’s an experimental side, there’s a curiosity. All that is more intriguing to me than knowing, headstrong, oozing sexuality.”

Jacobs looks younger than 42—maybe it’s just the way he’s dressed, or his trendy plastic eyeglass frames; maybe it’s the way he sits in his chair, casually leaning over and stretching, yawning, and squirming in his seat. The icons he offers are of a nostalgic sort: camp counselors, teachers. He evokes that feeling of being a lost teenager—which, of course, Jacobs was. There’s a certain Spielbergian mythmaking at work with Jacobs’s style, a yearning for the uncomfortable suburban comfort of an American kid in the seventies. “What’s comfortable to me is familiarity,” he says. “Comfort has nothing to do with the size of the garment. I do find something quite comfortable and charming in a too-narrow shoulder, a sleeve that’s too short or too long, a pant that’s too high or too low, hems that are trod on. I like romantic allusions to the past: what the babysitter wore, what the art teacher wore, what I wore during my experimental days in fashion when I was going to the Mudd Club and wanted to be a New Wave kid or a punk kid but was really a poseur. It’s the awkwardness of posing and feeling like I was in, but I never was in. Awkwardness gives me great comfort. I’ve never been cool, but I’ve felt cool. I’ve been in the cool place, but I wasn’t really cool—I was trying to pass for hip or cool. It’s the awkwardness that’s nice.”