|

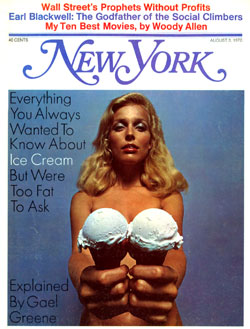

From the August 3, 1970 issue of New York Magazine.

Ice cream unleashes the uninhibited-eight-year-old's sensual greed that lurks within the best of us. I do not celebrate the Spartan scoop of vanilla the incurably constricted grownup suffers to cap a pedestrian dinner. I sing of great gobs of mellow mint chip slopping onto your wrist as your tongue flicks out to gather the sprinkles. I sing of champagne and rum raisin and two spoons in bed on New Year's Eve. I sing of the do-it-yourself-sundae freakout with a discriminating collector's hoard of haute toppings—wet walnuts, hot fudge, homemade peach conserve, Nesselrode, marrons and brandied cherry—whisk-whipped cream, a rainbow of sprinkles and crystals and crisp toasted almonds, inspiring a madness that lifts masks, shatters false dignity and bridges all generation gaps.

Grownups who never eat ice cream are instantly suspect.

They probably hate sand, sleep in pajamas, never eat spareribs and kiss with their mouths closed. What are they trying to hide?

New York is in the full throes of an ice cream renaissance. The hand-dipped ice cream cone market is highly bullish. Barricini began hawking "the biggest dip in town," 25 cents a cone, free sprinkles, in its candy shops this summer. Lines formed. Queues began to tail around the corner. Inspired, Chock Full O' Nuts began selling cones in certain bellwether outlets. Barton's was not blind. A crash campaign to meet the hand-dipping competition in selected stores is in the final countdown . . . and Barton's vows to grace Brooklyn's Kings Plaza Shopping Center with "a major ice cream parlor" by the end of August. Carvel braced to survive the promised invasion of Baskin-Robbins. Yum Yum conspired to topple them all. And Häagen-Dazs infuriated rival ice cream makers by breaking all the rules at 85 cents a pint.

In these harsh and uncertain times, as the establishment cracks and institutions crumble, it is no wonder we reach out to ice cream. It is a link to innocence and security, healing, soothing, wholesome . . . the last of the eternal verities. Or is it?

Little girls are made of sugar and spice and everything nice.

Ice cream ought to be too. Alas, it is not.

Most ice cream sold today is sadly "mock." It is half air and almost totally synthetic, laced with seaweed, gum acacia, locust bean gum and such chemical goodies as propylene glycol (an antifreeze), glycerin, sodium car-boxy methylcellulose, monoglycerides, diglycerides, disodium phosphate, tetrasodium pyrophosphate, polysorbate 80 and dioctyl sodium sulfosuccinate—all these to "stabilize" and "emulsify." All is fair to cut costs: dried eggs, dried milk, whey, corn syrup instead of sugar, the cheapest artificial flavoring.

Government standards set a few minimums: 10 per cent butterfat and no more than 50 per cent air (what the industry refers to as 100 per cent overrun). A half-gallon must weigh at least two and a half pounds. The only information the law demands on the label is evidence of artificial flavoring.

Ice cream makers have been backed against the wall by supermarket muscle, their own merchandising traditions and the public's indifference to quality:

"When we put $100,000-worth of freezers into a supermarket chain that buys our ice cream, the supermarket can name the price. If they demand a 69-cent half gallon, we've got to produce it or get our freezers out."

One cunning economy pursued by ice cream makers was to re-import at a pittance surplus American butter shipped overseas as part of the government's dairy price support program. When dairy lobbyists got the government to outlaw the practice, ice cream makers found a new loophole: Canadian ice cream. It comes in duty-free, 40 per cent butterfat, made from guess-who's surplus butter . . . and is reblended to meet commercial ice cream standards. Today's store-bought "home-made" ice creams are likely to be blends of dairy mix and canned flavorings, varying in integrity.

Ice cream is like wine. It ranges from the meanest vin ordinaire to the grand cru yield of the great chateaus. The best American ice cream is made from rich fresh cream (eggs if it is "French" ice cream), fresh fruit purée or cooked syrups, salt, sometimes gelatin, natural flavorings, fresh fruit and nuts. Manufacturers don't like to talk about air—it smacks of deceit. But when you hand-crank ice cream you are beating air into it. And air, at judiciously balanced levels, is what makes the classic American ice cream so smooth and creamy.

Too much air breeds anemia. Too little air makes a dense, soggy blend and, ice cream makers say, resists flavoring. Ice cream traditionalists frown on sharp deviations from this balance. That's why they snarl and rage over the success of "dense, soggy," low-overrun Häagen-Dazs. And they don't like seeing Häagen-Dazs' little tubs nestled in their own supermarket freezers.