|

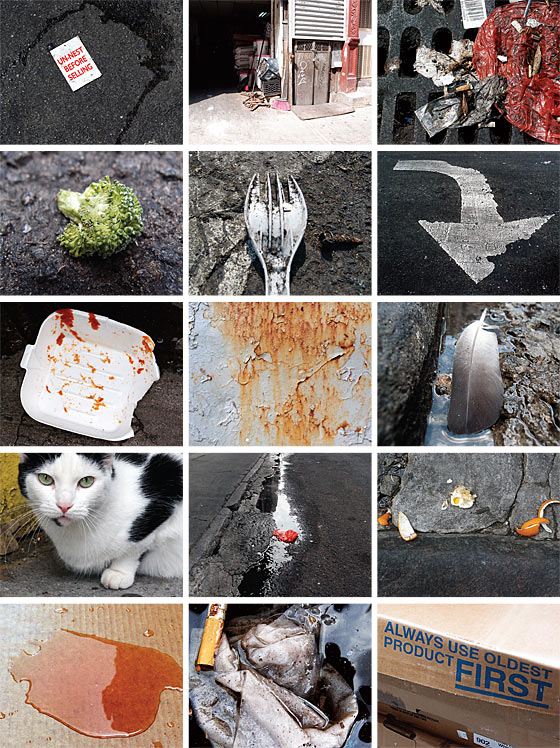

Broome Street between Allen and Eldridge on a recent afternoon.

(Photo: Jake Chessum) |

Sewer workers in 1910 had a nickname for the mold that grew in Lower East Side sewers. “Lace curtains,” they called it, because the stuff was white and draped prettily across the sewer arcs. At a time when the city was steeped in filth—children romped in the slime of horse troughs, industrial rendering plants rendered—the Lower East Side was exceptional for its grease deposits, and smelled persistently of shit. There are no lace curtains to be found a century later, as the price of an apartment on Orchard Street indicates. If there’s any scent at all in 2011, it’s the scent of discretionary income: of gluten-free doughnuts, premium jeggings, artisanal cigars.

One particularly striking exception remains. It’s a mystery, the stretch of Broome Street between Allen and Eldridge—a quiet little block that smells like high meat and old squeegees. It gets bad in the spring and worse in the summer, when the smell of decay is overpowering. “Everyone around knows that block is the stinkiest block in all of Manhattan,” a resident named Kate told me. Elie Z. Perler, a neighbor who edits the website Bowery Boogie, agrees. “Not even the most disgusting subway smell compares,” he says. “I try not to eat while walking there, since I’d probably throw up.”

David Swanson, a former resident who has lived in several Third World cities, says he has never experienced anything like the “flushed-out catacomb” smell of the block, and it is true that the street’s stink has a menacing quality. To walk down Broome on an August afternoon is to spend a few minutes confronting the idea of dying, rotting, and smelling like Broome Street. The source of the smell is unknown.

Chandler Burr, the curator of the Department of Olfactory Art at the Museum of Arts and Design and former perfume critic for the New York Times, agreed to canvass the block with me on a recent damp morning in pursuit of clues. Starting on the western edge and moving east, the first thing Burr detected was food. “That’s a wok and hot oil,” he said, surveying the territory nose-first. “And a brown sauce. A generic Hunan sauce.”

We walked east. “Now cabbage,” Burr said. “Chinese cabbage.”

An elderly lady down the street pulled a cart in our direction, looking frail but moving fast. With her free hand, she pressed a folded paper towel across her nose.

“Holy shit, that’s urine,” said Burr. “That’s urine. Human urine. That’s like, you’ve got your face in the urinal.”

He stopped to inhale. The urine was presently replaced with the smell of cigarette smoke and Tide detergent, both wafting from a bodega. It was tough to localize the urine. Burr kept going until a current of the signature Broome odor whistled past.

“Whoa,” he said, stopping on a dime. “Cat urine. Wet dog. Live dog. It’s that,” he said, pointing to an open warehouse at 284 Broome Street. We vectored over to the threshold of the warehouse, which was open to stacks of boxed rice, paper towels, and cabbage. The odor didn’t seem to involve any of these things. It was ripe and outlandish in a way that made a person feel perverted.

“Unbelievable,” said Burr, shaking his head. “Absolutely unbelievable.”

A man sitting inside the warehouse waved at us.

“I can’t believe they let a person sit in there,” Burr murmured.

Could this curator of the Department of Olfactory Art identify the source of the smell?

Burr shook his head grimly. “I have absolutely no idea.”

The following week, I met Avery Gilbert, an expert in odor perception and the author of What the Nose Knows: The Science of Scent in Everyday Life, on Broome with a similar plan in mind. He directed my attention to a gutter with a sock floating in it and diagnosed standing water as the area’s first problem. “It’s a bacterial broth,” he said. “There’s a nice oily sheen to this one. Smells like rotten vegetables.” The air was a mesh of flies. At 284 Broome, the warehouse was doing a slow Saturday business, and as we approached the building, Gilbert replicated Burr’s body language. “Ay-yi-yi,” he said. “Wow. Oh, boy. Oh, boy.”

The smell was so bad he began to laugh.

“It’s like a litter box,” Gilbert said. “Cat urine. Cats.”

Cats!

So, I questioned, the smell is cats? Cats in large quantities?

But he wasn’t so sure. “It’s hard to determine without seeing,” he said. “So much depends on the context.” I nodded, grateful that at least Burr and Gilbert had succeeded in pinpointing 284 Broome as the source of the odor. Scanning the area for leads, I noticed a cellar stairway adjacent to the warehouse. It was slicked with graffiti, dust, and stickers reading CHICKEN WITH GIBLETS and CHICKEN WITHOUT GIBLETS. When I showed Gilbert the stickers, his eyes narrowed. A forklift beeped in the distance.