|

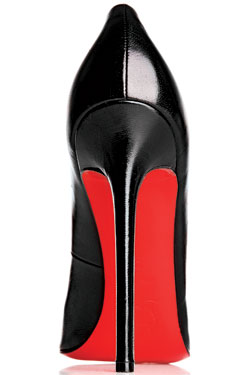

Louboutin's "Pigalle" shoe.

(Photo: Danny Kim) |

In 1992, Christian Louboutin saw his assistant painting her nails red, and swiped the color to varnish the bottoms of a pair of shoes he felt “lacked energy.” He has used red soles ever since.

In 2008, Christian Louboutin SA obtained a trademark in the U.S. for what the designer termed his “signature soles.” Then, on April 7 of this year, Louboutin sued Yves Saint Laurent for trademark infringement after failed attempts to persuade it to pull red-soled 2011 cruise footwear from stores. Calling YSL’s soles “virtually identical” to their client’s, Louboutin’s lawyers requested a preliminary injunction against sales of the shoes, as well as damages of at least $1 million. YSL, which has used red soles since the seventies, refused, and the case went forward. According to professor Susan Scafidi of Fordham Law School’s Fashion Law Institute, cases like this are rare because luxury companies typically rely on the press to point out when one high-end designer copies another. “A couple of years ago, for example, Armani charged that Dolce & Gabbana had copied a pair of quilted men’s trousers, and the images immediately echoed through the blogosphere,” she says. An unbecoming lawsuit isn’t worth the trouble, since “the fashion community has already delivered a reputational slap on the wrist.”

Last Wednesday, Judge Victor Marrero rejected the preliminary-injunction request. In the fashion industry, he wrote, color “serves ornamental and aesthetic functions vital to robust competition.” Marrero noted that even if Louboutin’s red outsole has gained enough public recognition to acquire secondary meaning, Louboutin is unlikely to be able to prove that it is entitled to trademark protection.

But will Louboutin kick back?

LOUBOUTIN’S CASE

“It is the obligation of the second comer to take all appropriate steps to avoid any likelihood of confusion with the first mark.” —Louboutin lawyer Harley Lewin, of McCarter & English LLP

1. Louboutin’s case is anchored by its registered trademark. Just as Lacoste labels its shirts with an alligator, red lacquered soles indicate that the shoes are Louboutins, according to trademark documents. To prove to the trademark office that the red sole was more than just an element of a nice-looking shoe—and thus a trademarkable “sign”—Louboutin compiled over a hundred articles and editorials (including pieces in The New Yorker and the International Herald Tribune) that noted his shoes’ unmistakable signature soles. Lewin explained, “Because of the enormous media coverage of Christian’s shoes, there’s an association in the mind of the public of a bright-red lacquered sole. It works the same way—if not even more loudly—as if his name were printed on the sole of the shoe in big letters.”

2. “Consumer confusion” is a key part of trademark cases. Louboutin and YSL attract a very similar clientele and are sometimes displayed quite near each other in department stores. There is also the hypothetical possibility of losing potential customers before the point of sale: You dislike a pair of shoes that you see someone wearing on the street and notice they have red soles; you assume they’re Louboutins and form a negative impression of the brand.

3. Louboutin’s lawyers commissioned a survey to see if consumers would mistake YSL’s red-soled shoes for Louboutin’s. They presented photographs of YSL’s shoes to a pool of consumers and asked who they thought had made them. Forty-seven percent answered “Louboutin,” and of that group, 96 percent said they named Louboutin because of the sole.

4. Although YSL claims to have been making red-soled shoes for years, all the ones it has made since Louboutin’s trademark registration have either been too obscure (sold in tiny batches) or not close enough to Louboutin’s red to cause concern.

LEWIN’S RESPONSE TO JUDGE MARRERO’S RULING

“While [Marrero] acknowledges the fashion industry at large has recognized the Louboutin Red Sole as a trademark source indicator, he has concluded that the industry needs to use colors on outsoles without restriction … We will evaluate all the alternatives available in the days to come.”

YSL’S CASE

“YSL does not have respect for a claim that Louboutin alone is allowed to use red as a design element on an article of fashion. No one designer should be able to monopolize a primary color for an article of clothing.”—YSL lawyer David Bernstein, of Debevoise & Plimpton LLP

1. Louboutin never should have gotten permission to trademark red soles to begin with, because it’s an ornamental design element that can enhance the aesthetic appeal of footwear. Louboutin’s trademark was rejected by the U.S. trademark office in 2002—only to be accepted six years later. “In our view, that was a mistake,” said Bernstein. “People do sometimes get trademarks that never should have been registered, and it is very common to challenge a trademark and have it canceled if it was inappropriately registered.”

2. “Many people are certainly aware that Louboutin shoes have a red sole, but that doesn’t mean that he’s the only one who can use it,” said Bernstein, adding that YSL chose to use red soles for its 2011 cruise collection because the company wanted to make monochromatic shoes that would match the red color palette for the season.“The idea of doing a monochromatic shoe is one that YSL’s designers repeatedly come back to. It’s a classic, revered design tradition there.” What’s more, one of the shoes with red soles was a Tribute sandal, an iconic YSL shoe. “No one could look at a Tribute and not recognize it as a YSL.”

3. The survey conducted by Louboutin’s lawyers showed only the red outsoles of the shoes, not any other portion of it (Bernstein described it as “deceptive”). When YSL’s lawyers conducted a similar survey, they showed a video of a woman walking around in the shoes. Less than 5 percent identified the shoes as Louboutin.

4. YSL has been making and selling red-soled shoes since the seventies, so it was odd that Louboutin decided to sue now.

BERNSTEIN’S RESPONSE TO JUDGE MARRERO’S RULING

“We’re gratified that Judge Marrero has agreed with YSL that no designer should be allowed to monopolize a single color for an article of apparel. As Judge Marrero indicated, YSL designers are artists, and like other artists, they should have the right to use the full palette of colors.”

Other Fashion Trademarks

|

(Photo: Amy Strycula/Alamy) |

Color

• Tiffany & Co.’s blue box

• Hermès’s orange

Other marks

• Adidas’s stripes

• Levi’s red tab

• Tommy Hilfiger’s flag

• Ralph Lauren’s polo player

Other Fashion Trademarks

• Adidas v. Payless

Payless was creating sneakers with two and four stripes—not Adidas’s classic three—but a jury found that the chain was still ripping off the sneaker company’s design and awarded a record $305 million to Adidas.

• Calvin Klein Cosmetics v. Parfums de Coeur

Parfums de Coeur, the company behind a perfume line actually marketed as Designer Imposters, came up with a scent called Confess, whose tagline was “If you like Obsession by Calvin Klein, you’ll love Confess.” Calvin Klein didn’t love it, but still lost its case when the court ruled that no consumer would confuse the two products given the designer-imposter disclaimer—and that comparison tactics are well-known in the world of marketing.