|

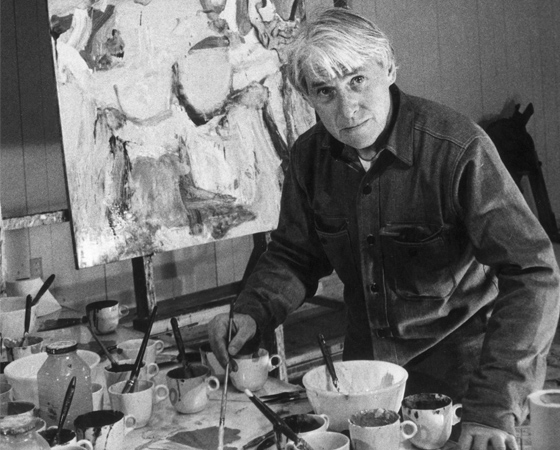

De Kooning in his Long Island studio, 1967.

(Photo: Ben Van Meerondonk/Hulton Archive/Getty Images) |

Jerry Saltz: Mark, the Willem de Kooning biography you and your wife, Annalyn Swan, wrote gave me the most vivid picture of the mid-century New York art world I’ve ever had. One thing that really struck me was the severe poverty these guys experienced—how it seemed to define their whole lives. De Kooning didn’t have a phone until the sixties; he had no bank account. Most of them achieved success later than almost any artistic generation ever. What did this poverty cost them?

Mark Stevens: Depends on the artist. Gorky found the poverty and lack of recognition soul-crushing. De Kooning suffered too, but he also knew how to be poor. He’d grown up rough, scraping by. He was resourceful. He used to say, “I’m not poor. I’m broke.” I hate it when people make a romance of the garret, but the struggle probably made that generation—or at least the best artists of that generation—unusually serious and committed to their work. They had bet their lives.

J.S.: True. Though it really made some of them unbearable windbags. When I think about Barnett Newman blathering on about “the sublime” …

M.S.: When no one’s listening, you fall in love with your own voice.

J.S.: When I came of age, de Kooning was always attacked as a sexist pig who slept with everybody and painted women to look like crazed gargoyles. Yet your book talks about how his wife, Elaine, slept around, and he caught her twice in bed with other men—once with his own art dealer, another time with his staunchest defender, Thomas Hess. For me, the paintings aren’t sexist; they’re sexy—luscious, fleshy, wild life.

M.S.: Who would you have him paint, Margaret Mead?

J.S.: Well, John Currin has painted Bea Arthur and Nadine Gordimer …

M.S.: Calling de Kooning misogynist is simpleminded. It’s for the finger waggers. It caricatures a complicated sensibility. Sure, anger is there, but so is love, desperation, tenderness, joy, and hilarity. Sometimes crazily all at once. Sometimes in varying proportions. “Beauty makes me feel petulant,” he once said. “I prefer the grotesque. It’s more joyous.”

J.S.: Well, he also said, “I’m cunt-crazy!” to some cretin who pointed at a red gash in a crotch and asked him, “What’s that?”

M.S.: The hilarity—the scary hilarity—of some of his women paintings is underrated. In the fifties you saw women walking down the street in lipstick and heels wearing—around their necks!—dead foxes with scrunched-up heads and little paws. And by the way, the several very important women in de Kooning’s life with whom he had long-term relationships—and most of them were very bright—did not regret the time spent.

J.S.: Art critics can be such idiots. They loved de Kooning in the forties. Then he changed direction in 1950 and started painting women, and Clement Greenberg turned on him. They all claimed that de Kooning was violating the rules of artistic progress. Such crap!

M.S.: Greenberg was a great critic, but not one to let a painting get in the way of his ideas. He loved to play the part of the hanging judge, regretfully executing artists who fell afoul of serious taste.

J.S.: For me, de Kooning proves that the idea of the ever-forward march of modernism is a crock—that all art is contemporary art.

M.S.: Well, after 1950 de Kooning wasn’t interested in making a good painting, as that is conventionally understood. He said as much. He was interested in exploring, in seeing how far he could go with the paint, in finding new resolutions. He could have taken a nap, rested on his talent, seduced the critics, but he chose instead to make confrontational paintings that are like nothing else.

J.S.: I actually cried when I read the passage you and Annalyn wrote about the moment in 1953 when the young Robert Rauschenberg came to de Kooning’s studio and asked him for one of his drawings so he could erase it. One of the most pathos-filled moments in American art, to me, is when de Kooning says, “I know what you’re doing,” and adds, “I want to give you one that I’ll miss.” De Kooning works his whole life for a scrap of recognition; he gets it, and after 36 months he already knows his time is ending.

M.S.: That was tough, but he was tough. By the sixties, he was the artist you rejected in order to give your own art a generational edge. He became the necessary foil. He wasn’t happy about this, but he never tried to change with the times.

J.S.: Not only was everyone claiming that de Kooning was dead, they said painting was dead too! It’s like everyone wants to be an undertaker!