|

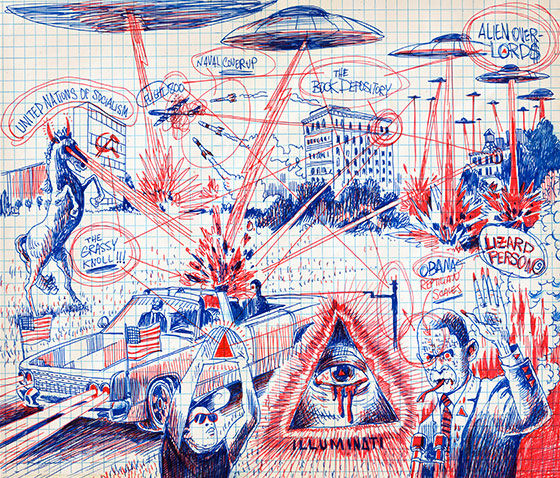

Illustration by Zohar Lazar

|

Every good conspiracy theory begins with the pawn. The more obscure and ordinary a figure, the slower he is to realize that his world is not as it appears, the better.

Consider, for instance, Ricky Donnell Ross circa 1980, a functionally illiterate black high-school dropout in South Los Angeles. These were still the boutique days of the crack epidemic, and Ross was a part-time dealer. Soon, though, he found a new supplier, a Nicaraguan man named Oscar Danilo Blandon, at which point Ross’s fortunes began to improve rapidly. Within two years, as drug use exploded and he supplied crack to both the Bloods and Crips, Ross became one of the dominant dealers in Los Angeles, moving 100 kilos each week, his network extending as far as southern Ohio.

Blandon was not any ordinary Nicaraguan man. He was a contra, a member of the militias organized and deployed by the CIA to overthrow the left-wing government in Managua. The contras had, it seems, long supplemented the funds Washington sent by helping Colombian traffickers ship cocaine north. A few years before he met Ross, Blandon had moved to California and, together with a group of ex-contras, was soon distributing the drug and using some of the revenue to support the movement back home. Ross did not know any of these details about Blandon, then. But because the CIA’s ties to the contras were extensive, and because of Ross’s pivotal role in the early crack trade in L.A., this episode soon became fuel for perhaps the last great conspiracy of the twentieth century: that the CIA had spread crack throughout America’s inner cities. Ross himself even seemed convinced. “Basically, I was selling drugs for the U.S. government,” he explained later, from prison, now a conspiracist, too.

The wider the aperture around this theory, the harder its proponents work to implicate Washington, the shakier it seems: After several trials and a great deal of inquiry, no one has been able to show that anyone in the CIA condoned what Blandon was doing, and it has never been clear exactly how strong Blandon’s ties to the contra leadership really were, anyway. But keep the aperture tighter, around Ross himself, and you see American intelligence officials working comfortably in close proximity to drug traffickers in Central America and a remarkably short chain from powerful figures in American intelligence to this crack dealer in Los Angeles. What is left is a general sense that something is amiss—that beneath the surface chaos of the early crack trade lies a deeper chaos that is political, that somewhere in the roundabout arrangement of influence in Central America a fist had, for a moment, come ungloved. If Ross sensed that he had been a pawn for forces he could barely understand, he probably wasn’t wrong. The question was: What forces?

That the Ricky Ross story follows a familiar plot, that we know what a pawn is and that we understand the patterns of conspiracy, owes a great deal to the Kennedy assassination, which took place 50 years ago this month and which gave birth to the modern golden age of conspiracy. The history of paranoia in America is long and magnificently florid: the witches burned in Salem; the Massachusetts colonists who built a settlement for Christian Indians, only to march all its residents to prison when suspicions grew that the converts were Satanist plotters in disguise; the society of stonemasons supposedly bent on controlling the government; the Bavarian liberals called the Illuminati, whose cabal was thought to have arranged the French Revolution and to be plotting something similar in the United States; the assassination of William McKinley, perhaps by Mark Twain. But in the frenzied speculation about who, exactly, killed John F. Kennedy, the modern conspiracy theory became itself: It acquired its cool, its documentary logic, its familiar cast of villains.

The seduction of conspiracy is the way it orders chaos. In the summer of 1964, the English philosopher and logician Bertrand Russell—past 90 years old then and possibly the most famously rational person on the planet—read the early accounts of the Warren Commission Report with mounting alarm. None of the important questions, he thought, were being answered. There was the matter of the parade route being changed without explanation at the last minute, so that the motorcade passed Lee Harvey Oswald’s workplace; the geometrically confounding arrangement of entry and exit wounds; the curious fact that an alibi witness who helped get an alternate suspect released from custody turned out to be a stripper at Jack Ruby’s club.

The logician went to work. Meticulously, Russell documented the discrepancies between each first-person account and the divergences between each report in the media. He gave his document a modest, scientific-sounding title (“16 Questions on the Assassination”) and a just-the-facts tone. This strange hybrid method, through which a literary genre convinces itself it is a science, has become not just a template for ornate conspiracies but a defining way in which American stories are told. In the English tradition of mysteries, the screenwriting guru Robert McKee explained a few years ago, “a murder is committed and the investigation drives inward: You know, you’ve got six possible murderers. In the American tradition, a murder is committed, we start to investigate, and it turns out to encompass all of society.” There is inevitably an intrigue that goes all the way to the White House. And conspiracy is not just how the disenfranchised view the powerful; sometimes, it is how the powerful view themselves. Secretary of State John Kerry recently admitted that he has long believed Oswald had not acted alone.

The stories told on our maniac fringe are not so different from an argument familiar from op-ed pages and Sunday talk shows—that in our zeal to hunt the enemies we see gathering on the horizon, we have committed torture, secretly spied on the innocent, and lost touch with our own principles. In the decades since the Kennedy assassination, American state power has extended around the globe, and simultaneously, the world has become more transparent: We are keeping, and leaking, many more secrets. And so conspiracy theories are no longer about religious cults, or foreign plots, or metaphysical incursions. They are instead about the national-security state, the FBI and the CIA, and the ways in which, in our hunt for conspiracies, we come to act like conspirators ourselves. “A fundamental paradox of the paranoid style is the imitation of the enemy,” the historian Richard Hofstadter famously wrote. The anti-masons had their own rituals and lodges. The anti-communists had secret propaganda arms, overseas fronts, and purges; the anti-Catholic Ku Klux Klan their priestlike robes. When the real-life CIA funded the contras’ rebellion in Nicaragua with money from weapons sales to the Iranians, when it spent years propping up the mad Nero of the cocaine traffic, Manuel Noriega, it seemed to have lost itself so completely that it was, in a sense, imitating the enemy. Why, then, should it be so implausible to think that some of its agents might have turned a blind eye to the small-fry moves, in the same spirit, of Oscar Danilo Blandon?

Conspiracists are by nature anti-heroic—they believe that faceless networks must be far more powerful than ordinary individuals. A marginal figure like Ross could never have built his cocaine empire alone; Oswald could not have killed a president; a few dozen men in Afghan caves could not have brought down the Twin Towers. The romance of the conspiracy hunt lies in the way it transfers vitality from the assassin to the buff, at home alone, searching for the plot’s true source. In this, it matches perfectly the romance of the Internet, which perhaps explains why conspiracy has found such a resolute home there. If Ross, Oswald, and Hani Hanjour are merely pawns, then the story needs a hero, and the puzzle-solver himself raises his hand.