|

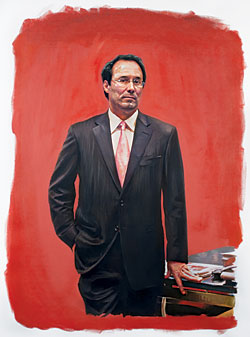

Painting by Diego Gravinese/Thatcher Projects, NYC.

|

“I’m not Greta Garbo,” says Gary Barnett of Extell company, a developer of luxury Manhattan buildings and just about the only builder of consequence who hasn’t been stopped by the crash. While Barnett is an increasingly visible presence on the Manhattan skyline, most of his life is elsewhere. An Orthodox Jew and father of ten children, he lives in Queens and guards his privacy obsessively. In a recent Crain’s article, he refused to divulge his age (he is 54). “It’s not like I’m frightened of the camera,” he continues. “I’m not Howard Hughes. It’s not that I hate publicity because I hate publicity. It’s that I don’t see any good use of it. Donald Trump sells buildings that way, or he gets a television show and makes money off it. But that doesn’t do anything for me.”

Barnett is the anti-Trump. His buildings are as ostentatious as he is unassuming. Extell, which Barnett founded in the early nineties after a career as a diamond trader in Belgium, is emblematic of a new type of New York real-estate firm that specializes in developing ultraluxury buildings that are akin to gated communities in the sky, where buyers with millions to spend can satisfy nearly any desire without ever stepping outside. His condos, like the 60-story Orion on West 42nd Street or the Ariel towers on Broadway at 99th Street, include such extravagances as indoor lap pools, spas, screening rooms, and pet salons. Barnett’s particular vision for urban living now appears wildly out of touch with current economic realities—and yet he continues to sell properties to buyers who, so far at least, have been insulated from the ravages of the recession. “He has a really strong stomach,” Corcoran CEO Pamela Liebman says. “He shows no fear.”

Barnett’s lone-wolf style has not exactly endeared him to his peers. New York real estate has long attracted players who view business as both a commercial and a civic pursuit. Jerry Speyer, the co-CEO of Tishman Speyer, is perhaps the most famous archetype of the New York macher, serving as a confidant to mayors and governors. Inside the fishbowl of New York real estate, Barnett has few friends. He’s a subject of fascination and derision, a combative figure who is unafraid to challenge the industry order. Since blasting onto the scene at the start of the last decade, he has clashed with Bruce Ratner and the New York Times for control of the land under the Times’ new Eighth Avenue headquarters and made a surprise eleventh-hour bid for Atlantic Yards just as Ratner thought the massive development project was in his grasp. And now that the boom is over, Barnett is even more out of step with his peers. While few other developers are building, Barnett is charging ahead with projects that are grander than anything conceived at the market’s vertiginous peak. In March of this year, he snapped up the Helmsley Carlton House at 680 Madison Avenue for $170 million, vastly outbidding other suitors. And, in an act of either extreme confidence or epic folly (or both), Extell recently started construction on a project called Carnegie 57, a 1,000-foot-tall, $1.3 billion condo and hotel designed by Christian de Portzamparc and backed by the investment arm of the Abu Dhabi royal family. When completed in 2013, Carnegie 57 will top Trump’s U.N. Plaza tower for bragging rights as the city’s tallest residential building. “There’s a resentment that he’s able to still build and doesn’t give the appearance that he’s affected by this market,” says Stuart Saft, a partner at Dewey & LeBoeuf.

The resentment is tempered by the fact that many of his peers expect him to fail. “You have to bet that the peak will be higher than it’s ever been,” one incredulous real-estate banker said. “It’s a huge bet.”

“I don’t see there being significant competition for what we’re doing,” Barnett tells me. Barnett is standing at a conference table in his corner office, flipping through a glossy prospectus with renderings of the Carnegie 57 tower—a real-estate fairy tale in blue glass, punching out of a scrum of midtown skyscrapers. “I hate to speak in hyperbole, but I think it’s going to be the nicest project done in the city, because the architecture is beautiful,” Barnett says, sounding, it must be said, more like Trump than usual.

Barnett claims that irrational exuberance is not involved in his building spree. “There’s no new inventory coming to market,” he says. “If you go around, there’s a lot of pieces of dirt that didn’t get built. When this thing crashed, there wasn’t tons of overhang of inventory. If the bubble had continued for another two or three years, it might have been really bad.”