|

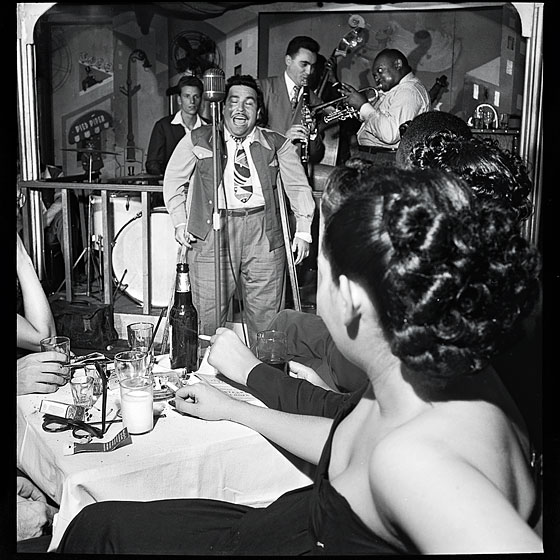

At the Pied Piper, 1947.

(Photo: William Gottlieb/ Library of Congress) |

B rando on Broadway in Streetcar, the same year All My Sons, Brigadoon, and Finian’s Rainbow opened for business. Miles and Bird and Billie on 52nd Street. Bruno Walter at Carnegie in front of the New York Phil, Toscanini over at Rockefeller Center leading the NBC Symphony, a rookie named Jackie Robinson racing into history in Brooklyn. How could any New York be better?

The end of the war had initiated an unprecedented economic expansion, which was in turn italicized by a degree of national self-confidence almost impossible to fathom today. America believed in its future, and as it usually did back then, it watched New York to see how life could be lived.

In 1947, New Yorkers could put as much faith in local government as they had placed in Washington during the war. Never was this clearer than in April, when the city Health Department responded to a smallpox scare with staggering efficiency, administering 1.2 million vaccinations within days and more than 6 million in a month. No one with a smart kid questioned the quality of the city’s public-school system. That year, the student body of the Bronx High School of Science included four future Nobel laureates (not to mention E. L. Doctorow and William Safire).

Beneath the hurrying streets, where newsboys hawked ten daily papers, a spic-and-span subway system welcomed 2 billion passengers, the most ever. The price of a cane seat, or at least a firm grip on a leather strap? One nickel—the 2011 equivalent of 49 cents. At Grand Central every evening at six, New Yorkers with deeper pockets and distant destinations boarded the Twentieth Century Limited along “the quay”—the Twentieth’s own platform, garlanded with a carpet of crimson and gray. At the head of the train, the Henry Dreyfuss–designed beauty of a locomotive strained at its leash, ready to charge west.

New York is never perfect, and it wasn’t in 1947. Residential segregation was ubiquitous; even the new rent-stabilized Stuyvesant Town was closed to blacks (and unmarried whites). Robert Moses continued his destructive assault on the physical city. Mayor William O’Dwyer would soon skip town on the wings of a convenient ambassadorship just before a vast corruption scandal erupted in the NYPD.

But the Wonder City, as some contemporaries called it, had never been, nor ever again would be, quite as wonderful as it was in that postwar dawn. Penn Station still soared. Harold Ross still edited The New Yorker. And one of that magazine’s treasures, E. B. White, would soon write, “No one should come to New York to live unless he is willing to be lucky.” In 1947, the luck was here for the taking.