|

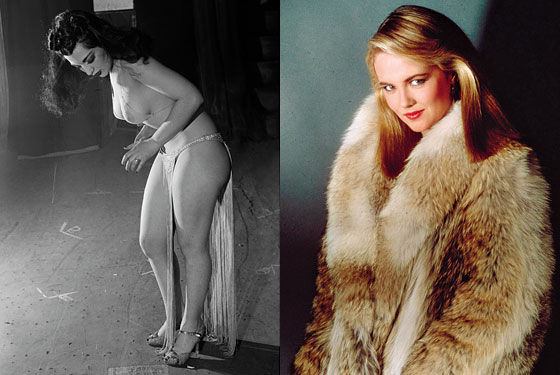

Sherry Britton, 1940; Cornelia Guest, 1983.

(Photo: Bettmann/Corbis; Unimed/Rex USA) |

BURLESQUE DANCER

By Liz Goldwyn

author, Pretty Things

Part of the appeal of the burlesque queens of the thirties and forties was that they were kind of approachable, even a little bit rough around the edges. But Sherry Britton wasn’t like that—she was a diva. She behaved as though she were too good for burlesque, and that created a fantasy: that Sherry was a princess who just happened to be traipsing across the boards of the Bowery, regal even when she was balancing two glasses of water on her breasts. Of course, backstage she would get into knockdown, drag-out fights with other queens like Margie Hart, and her sexual affairs were legendary. But even so, Sherry had this air of dignity and grace: She was a star, and she had the attitude of a star.

DEBUTANTE

By William Norwich

Doris Duke was introduced to society in 1930, at age 18, and presented at no lesser place than Buckingham Palace. But her heart just wasn’t in it. Brenda Frazier was fabulous. Secretly, though, she was miserable, and confessed the sorrow of it all to Life magazine in 1963. Beautiful Jacqueline Bouvier did it for her family and thought it was all pretty silly. So the tiara goes to Cornelia Guest, the postmodern, modern deb who not only had a ball, or several, but also managed to curtsy her way from real palaces to disco palaces, creating the template for today’s industrial-strength celebutantes—like Kim Kardashian. And she got home in one piece, several years ago, to Templeton, the 28-room family house, stables, and gardens in Old Westbury. “As my mother says,” Cornelia said in 2001, quoting her beloved mother, C. Z. Guest, two years before C.Z. died, “anybody can go off. The trick is coming back.”

DISH

By Adam Platt

The Oyster Bar pan roast—still being served at the Oyster Bar in the bowels of Grand Central—is a silky concoction, thicker than soup but gentler than a stew. It’s made with half a dozen Bluepoints, sweet butter, a dash of secret chile sauce, and flagons of country cream, all poured over a comforting mattress of soggy toast. I would argue that it’s grander than that other great New York icon the pastrami sandwich on rye, more versatile than eggs Benedict (invented at the Waldorf-Astoria) or the porterhouse steak, and heartier than vichyssoise soup, which the great chef Louis Diat first served at the Ritz-Carlton Hotel on 46th Street in 1917. The last time I enjoyed it, the steamy bowl took exactly four minutes to reach my place at the bar, which is more or less what you’d expect for the greatest New York restaurant dish of all time. In that magisterial, eternally bustling room full of strangers, it tasted exactly the way it did when I ordered it for the first time, 40 years ago, with my grandfather, a lifelong New Yorker: opulent, mysteriously spicy, and faintly like the sea.

|

J. P. Morgan, 1911.

(Photo: Courtesy of Library of Congress) |

FINANCIER

By Felix Rohatyn

There have been other titans, Henry Ford and John D. Rockefeller in particular, but no one has come close to J. P. Morgan’s capabilities. He saved the financial system in 1907 by inviting the leading business figures of the day to his home. Then he locked them in until they committed themselves to the rescue.