|

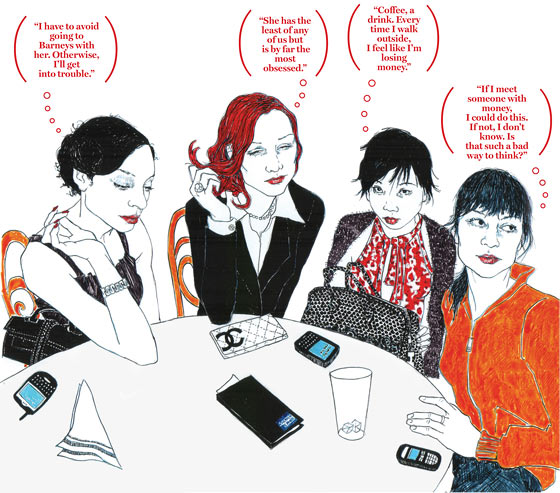

Illustration by Hope Gangloff, Art Department

|

'I’m feeling very uncomfortable about your apartment,” said Liz. She was talking to her best friend, Sara, who at the age of 24 had just purchased a cozy one-bedroom (price: $675,000) on the Upper East Side. They were on their way to dinner, two carefully groomed, impeccably dressed young women trying to hail a cab, when Liz’s remark just kind of … slipped out. Sara was startled—“I guess it had just been in her head for so long,” she later told me—though she knew something had been brewing. Until she bought the apartment, it had been easy—and convenient—to overlook how different their lives were becoming. They had known each other since their freshman year at Stuyvesant and had attended the University of Pennsylvania together; they recognized each other immediately as similar products of middle-class Jewish households (Liz grew up on East 18th Street, Sara in Brooklyn) in which a great deal of pressure was put on them to succeed. They spent practically every other day together, talking about books or politics or going out and buying each other rounds of overpriced cocktails and feeling the particular bond of being young in New York City. But now there was this apartment, this doorman building with decent views, starkly highlighting certain developments in their lives. Namely, that Sara was making money and Liz was not.

This was just over a year ago. As they told me the story recently over dinner—gourmet takeout and red wine—at, yes, Sara’s apartment, they laughed about it, emphasizing the whole ordeal as a purely past-tense affair.

Liz: “It was just growing pains.”

Sara: “A dissociation of our lives.”

Liz: “It’s hard. You have these feelings you don’t want to have. It helped just being able to say, ‘I’m envious. I’m proud of you, but I’m jealous.’ ”

The dinner was one of several conversations I had with them as a means of dissecting a pernicious, rarely discussed drama among friends: the way money bores into the dynamic and disrupts fragile equilibriums. I met them after sending out an e-mail to friends and acquaintances asking if anyone knew a group with the “sense of humor” required to talk openly about money. The responses ranged from the anxious (“I wouldn’t know where to start”) to the vaguely accusatory (“Are you insane?”), but a few were willing to go along with it. In addition to Liz and Sara (who asked to be called by her Hebrew name), I also spent time with their close friends Alex and Michelle (who asked to go by her middle name) and met another member of the group whom I’ll refer to as Miss X (she both comes from serious money and makes serious money and elected not to participate in an article on the subject). Like many friends in New York, they’re bound by a paradox: living similar lifestyles on massively diverging budgets. As a Ph.D. candidate in neuroscience at Rockefeller University, Liz receives a $23,000 annual stipend; Sara works in finance, in a job where she can expect a significant raise every year or so, and now earns what she describes as a “low to mid” six-figure salary. Both Alex and Michelle work in advertising, earning “mid to upper” five-figure salaries, though Alex, a fellow Penn alum, has years of loans to pay off.

Genuine friendships are a connection, of course, not a transaction. But in a city where money has a way of becoming the subtext of every exchange—where just choosing a restaurant can carry relationship-straining implications—certain snags and fissures are inevitable. Take Sara and Liz. It’s one thing for Liz to have admitted jealousy, another to eradicate it. Ever since the apartment became an issue, Liz has developed a habit of turning almost any topic into a conversation about money—specifically, about everyone in New York having more than her—which wears thin on Sara. (“Liz has the least of any of us,” Sara told me privately, “but is by far the most obsessed.”) They both admit that they no longer see each other as often, that they are not quite as open as they used to be, and that, for better or worse, they understand why. Though they grew up in the same city, they have come to inhabit entirely different New Yorks.

As if to illustrate this, Liz invited me to see her apartment after dinner at Sara’s. “Just so you can compare and contrast,” she said as we walked down East End Avenue and through the gates of Rockefeller University—only a few blocks but many psychic miles away from Sara’s. Liz lives in student housing, which she sublets when she’s out of town to help pay for vacations like the trip to Spain she took with Sara and Alex a couple of years ago. The fluorescent-lit, linoleum-floored one-bedroom, furnished in Classic American Dorm Room style, is spacious by New York standards, 500 square feet or so, but it’s a space in which it is almost physically impossible to feel like an adult. For Liz, who is 26, I can imagine this getting old.