|

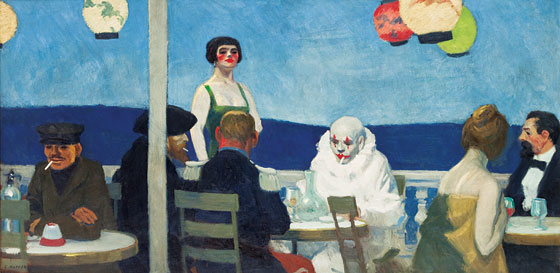

Hopper's Soir Bleu (1914).

(Photo: Sheldan C. Collins; Courtesy of ©Heirs of Josephine N. Hopper, Licensed by the Whitney Museum of American Art) |

Edward Hopper, viewed a certain way, becomes a dear old chestnut. Rooftops, lonely girls, railroad tracks, gas stations (those queer old pumps), soda fountains, spooky-quaint houses. A melancholy Norman Rockwell. He can be used to conceal a cranky dislike for abstract, modern, and contemporary art—Hopper himself didn’t think much of the Picassos and Pollocks of the world—and he remains, as always, good box office. The Whitney, often rebuked for being trendily obscure, all but owns the Hopper franchise. Shouldn’t the museum enjoy a moment of rest, reputation, and the elderly paying customer?

Inevitably “Modern Life: Edward Hopper and His Time,” organized by Barbara Haskell and Sasha Nicholas, will have something of this cozy old-movie feel. Drawn almost entirely from the Whitney’s collection, the show is constructed around Hopper, but includes work from 34 other well-known artists who made their names before World War II and whose imagery is fairly realistic. (They range from John Sloan of the Ashcan School to the Precisionist Charles Sheeler.) The show intends to have a jangly urban emphasis, but the “modern life” invoked in the title obviously refers to a different modern than the one we know today. This is a survey of another, earlier America.

Yet the invitation to nostalgia—to an America when the modern still seemed homespun—need not be accepted. Because of Hopper. He is, despite the endearing retro bits, a great American pessimist who should particularly interest our own dispirited time. Hopper is both a dreamer and a dream-slayer; he stills fashion, hope, solace, and conviction. He did that in his era; he can do it now. Hopper, if provincial, is powerfully so. He sets today’s conventions, in art and elsewhere, into relief. He enriches the American darkness. Four words come to mind.

Silence. Contemporary culture would surely die of boredom if it were not noisy and discordant. Sound, in today’s New York, is often layered upon sound (an iPod on the subway). The art world, small as it is, hopes against hope that it will be loud. What a difference Hopper makes. In the neurological condition called synesthesia, the stimulation of one sense involuntarily elicits an experience in another sense. Where Hopper is concerned, we are all synesthetes: To see his paintings is to hear silence.

What other painter is so radically silent? In Vermeer, you can hear, distantly, Delft outside the door. Agnes Martin hums. The wheels turn softly in Robert Ryman. Hopper? Absolute silence, even in New York. In Rooftops, a watercolor from 1926 that’s in the Whitney’s show, the forms on a New York rooftop make up a crowd, but each form is also a silent single. The water towers aim away, the windows march in a line disconnectedly, and the curves try not to be noticed. When I think of city rooftops, I hear the sound of traffic below. Not when I look at Hopper’s New York.

There are many silences here, notably a silencing of irony. It’s difficult to imagine a world without irony; it seems indispensable today, or at least unavoidable. Irony even at its darkest and most despairing has a lightness: smarts, talk, spin, smiles, interpretation. Irony’s sound is that of intelligence at play. Hopper is strange enough to do without irony, mostly, and that can seem a kind of dumbness. As in struck dumb. That’s a silence the brilliant among us cannot use. It’s irreducible.

Isolation. This is a major theme in modern culture, of course, and critics today like to worry that the Internet—and its putative relationship-builders, Facebook and Twitter—represent new forms of dissociation. Perhaps they do; they certainly enlarge the small. But Hopper’s treatment of isolation is particularly acute. Not only are his pictures suffused with silence, his people cannot see or reach one another. In Soir Bleu, an early (1914) Hopper in the Whitney’s collection, seven people are grouped together, among them a clown who might ordinarily attract attention. Yet each of the seven finds a way to avoid the others. Their lack of connection is not pushed in the viewer’s face, as it might be by an ironist or expressionist. It just is.

Hopper treated sexual isolation with a kind of devastating tenderness. There was nothing slick or smart in his treatment of the body and its wants. Like a man afraid to touch, Hopper could never quite get a woman’s body right, and you wouldn’t want him to. The awkwardness has a mute eloquence. The brush is tight, self-conscious; the curves seem at once lubricious and strict. Hopper’s women (and the voyeur painting them) are glanced momentarily as they stare out windows or stand in door frames. In New York Interior, we face a woman’s back as she sews, one arm raised. Exactly what Hopper’s women want or think about is not clear; what’s certain is that, whatever the dream is, it’s beyond reach. In South Carolina Morning, from 1955, Hopper juxtaposed a woman in a doorway with a strangely abstract landscape. The dark horizon line holds no promise.