|

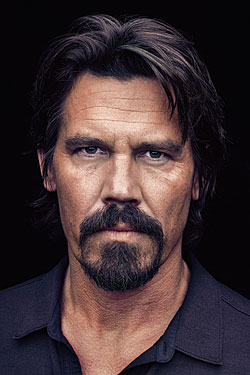

(Photo: Robert Maxwell; Grooming by Kim Verbeck/The Wall Group) |

The bro hug will come later—after the golf balls smacked at the Hudson; the 3,000 or so chain-smoked American Spirits; the near-erotic (“but not gay”) disrobing in the hotel room. But right now, Josh Brolin is contemplating my footwear.

It’s a Tuesday at lunch, and we’re supposed to be eating some expensive salads. But Brolin—chiseled and surfer-tanned—has dragged me from the frosty embrace of the Greenwich Hotel into the heat-wave chokehold of a Tribeca sidewalk to smoke a butt. “Ugly habit,” says the 42-year-old actor, running a hand through his dark brown rooster bangs. He talks fast and loose and unguarded—about his bad back, the bet he made with his brother that he could quit smoking (he did it for three months), how crazily, happily busy he is. It’s all a nervous-energy monologue until the shoes—mine, not his—pull him up short. “You see, man?” he says, squinting and pointing at my desert boots. “Same shoes as mine. Right? But those are what, 400 bucks? Because they’re designer?” I point out that I’ve had them five years, that the ladies love them, and—seriously?—they are vastly cooler than his knockoffs. He laughs. “Fucking New Yorkers.”

Brolin should know. Next month, in two unavoidable films, he will invade our civic ether by playing a pair of quintessential New York types: a Mephistophelian banker who manipulates careers and markets in Oliver Stone’s big-budget Wall Street: Money Never Sleeps; and a neurotic, cheating, narcissistic novelist in the Woody Allen comedy You Will Meet a Tall Dark Stranger. He will soon be unavoidable on our streets, too, when he shoots Men in Black III. To that end, he’s currently weighing his living options: Greenpoint, where his sister lives, or Tribeca, home to his hedge-fund friends.

Not bad for the former Goonies teen stud who had, until a few years ago, assumed the bulk of his income would come from his online day-trading. But then the Coen brothers yanked him from his brilliant supporting career to star in 2007’s No Country for Old Men. Of his current projects, Brolin is most nervous about the Allen film, because he doesn’t like the guy he plays. “Maybe it’s because I’m capable of being that selfish,” he says. “I was playing him and it was like, Yeah, that seems right and that seems organic. And that’s too bad, because if it seems organic then that means it exists in me. And I just wanted to slap myself. It’s pathetic.”

Brolin gained 30 pounds for Roy, a whiny, fulminating, beer-guzzling womanizer. Naomi Watts, who plays his gallery-assistant wife, says Brolin “was a wonderful wreck. He ate and smoked constantly. It was impressive.”

Before shooting began, Brolin had the bright idea that his character should be in a wheelchair. He wrote Allen a lengthy e-mail, to which Allen responded simply: “No.” The director is famously precise. “Once I used the word cannot instead of can’t,” Brolin says, swatting at a pigeon intent on landing on our table on the hotel’s patio. “And he pulled me aside and said, ‘You broke the contraction.’ And I’m like, ‘What?’ And he said, ‘You broke the contraction. See, it says right here in the script.’ I’m like, ‘Come on, Woody, you gotta be kidding me.’ He said, ‘No, it says here in the script can’t and you said cannot. You broke the contraction.’ ”

The pigeon, scrawny and mottled, nails its landing inches from Brolin’s lunch, and pings him with a red-eyed stare. “Look at this guy,” says the actor, lending the pigeon a Brooklyn-waterfront accent: “ ‘Hey, fuck you, lemme eat your sandwich. Turn your head, motherfucker. Light your cigarette. Go ahead.’ ”

Brolin was born into the acting life. His father, James, was on TV’s Marcus Welby, M.D. (a fact that got young Josh beaten up in school). His first role, in 1985’s The Goonies, seemed promising. The following year, he went up for the lead in 21 Jump Street, but his Los Angeles buddy Johnny Depp got it. He followed The Goonies with the skater flick Thrashin’ (skate or die!), which nearly ended his career right there. Brolin was totally bummed—not by the film, but by his horrendous acting. “I realized I wasn’t, you know, Leonardo DiCaprio,” he says. “It was awful, man.”

His big revelation came in the early nineties, courtesy of the underrated character actor Anthony Zerbe, who was an artistic director at the Geva Theatre in Rochester, New York. Brolin was living on the Upper West Side at the time and commuted upstate to perform with Zerbe. “He looked at me and said—actually he didn’t even say it, you just kind of felt it: ‘There’s a great character actor in you. They’re trying to make you something else.’ ”